Ricco/Maresca

529 West 20th Street, 3rd Floor

New York, NY 10011

212 627 4819

New York, NY 10011

212 627 4819

Following in the footsteps of the legendary New York art dealer Sidney Janis, Ricco/Maresca champions and showcases the art of self-taught masters working outside the continuum of art history. The gallery specializes in Outsider, Self-Taught, Contemporary, and historically significant American Folk art in various media.

Over a period of more than 40 years, Ricco/Maresca has helped blur the lines that have habitually separated conventional art-historical categories and “marginal” art. The gallery has carried out this mission through a pioneering program that emphasizes crossover between vernacular and mainstream traditions, the management of key estates (William Hawkins, Martín Ramírez, and Domingo Guccione among them), and seminal books produced with publishing partners such as Alfred A. Knopf, Little Brown and Company, Radius Books, and Pomegranate Press.

Ricco/Maresca Gallery was founded in 1979 on Broome Street, within New York’s then-emerging SoHo gallery district. The gallery relocated to TriBeCa in the 1980s and later moved to Wooster Street in SoHo—which had by then become an established contemporary art hub. In 1997, Ricco/Maresca became one of the first galleries to move to the new Chelsea art district and is currently located at 529 West 20th Street. The gallery participates and has participated in the ADAA Art Show, the Independent Art Fair, the Armory Show, Frieze Masters, Art Chicago, Art Miami, AIPAD, NADA House, and the Outsider Art Fair (New York and Paris). We work closely with major museums and collectors, and offer services that range from curatorial advisory to collection management, installation design, and conservation.

Artists Represented:

Gil Batle

Rosie Camanga

Tricia Cline

Kate Berry Brown

Hiroyuki Doi

Abigail Frankfurt

William I. Goldman

Ken Grimes

Domingo Guccione

The Artists of Gugging

Debbie Han

William Hawkins Estate

Alice Hope

Laura Craig Mcnellis

Mark Laver

Thomas Lyon Mills

Martín Ramírez Estate

Toni Ross

Beatrice Scaccia

Bastienne Schmidt

Günther Schützenhöfer

Hester Simpson

Max Streicher

Leopold Strobl

Lidia Syroka

Rebecca Norris Webb

George Widener

Works Available By:

Eddie Arning

William Butler

Henry Darger

Thornton Dial

Sam Doyle

William Edmondson

Morris Hirshfield

C.T. Mcclusky

Bill Traylor

Joseph Yoakum

Ricco/Maresca Gallery

Ricco/Maresca Gallery

Ricco/Maresca Gallery

Leopold Strobl

Leopold Strobl: Inner Realms

We are thrilled with the news of Leopold Strobl’s inclusion in the upcoming Venice Biennale (April 20 - November 24, 2024) as part of the exhibition “Foreigners Everywhere,” curated by Adriano Pedrosa at the 60th International Art Exhibition.

***

Strobl was born in Mistelbach, Lower Austria in 1960. He has been associated with the atelier at the Gugging Art Brut center in the outskirts of Vienna for over 15 years. Strobl’s USA debut took place at Ricco/Maresca, with an exhibition titled “Smallscapes” (April, 2016). Only two years later, as a result of our booth at the Independent Art Fair (March, 2018), five of his works were acquired by The Museum of Modern Art for their permanent collection. Strobl’s work has since gone into major collections worldwide.

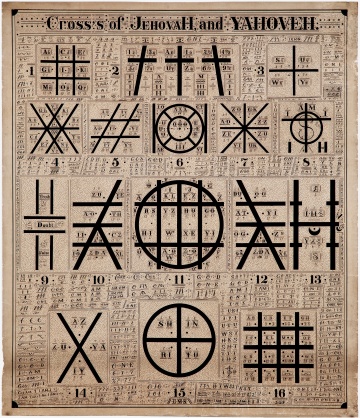

Constantine Karron

Constantine Karron: Kaleidoscopes

Constantine Karron was born Constantinos Demetryus Karazisis on March 15, 1897 in Greece. Little is known about his early life; he completed only a fourth-grade education as a child and immigrated to the United States as a teenager, arriving at Ellis Island, NY on February 28, 1914. Many young men left Greece in this year to avoid being drafted into the Ottoman Empire Army.

Karron next appears in records in Virginia, MN, a mining town on the “Iron Range”. The area was so named as mining of raw iron ore was the major industry of the region. First in the 1930 census as a roomer living in the house of a William Ager. He lived in another rooming house until 1940 when the census shows him at 205 1/2 Fifth Avenue South; this is likely where he produced his drawings. It is also where he died at age 75 in his single room, above what was then the Virginia Boat & Sporting Company. I came to have his work as he promised it to my mother, Rose Tuk, who was the store manager. She would often bring Karron food on holidays and watch him while he worked on his drawings—she very much admired his talent.

The 1940 census lists Karron as a Railroad Laborer. From his early employment, he seems to have had numerous jobs with the DM&IR (Duluth, Messabe, and Iron Range Railway). He was listed as a “signalman” and a “brakeman” at various times. He was always home in the evenings to work on his drawings or spend time in the library next door to his residence.

Shortly after Karron died in 1973, my mother brought a folder of his work to the Art Department of the University of Minnesota, Duluth. I was living in New York and had only her report of a show they mounted of some of his drawings. The show was reportedly done in collaboration with the Psychology Department. Based on the word lists included in the folder, some of the more bizarre images of faces, and the many, many “eyes” in all images, the evaluators speculated that he was likely an undiagnosed schizophrenic, paranoid type. I am a board certified psychiatrist, and I believe their speculations were very likely correct. It is a diagnosis consistent with what we know of his social isolation. He was also most likely to be meticulously accurate and precise in the work that he did for the railroad, as is reflected in his artwork. Despite a limited formal education, Karron was an avid reader, learning to speak excellent English with a wide vocabulary. His high intellect may have allowed him to hide evidence of any psychopathology from others.

— Pamela Ullman Call, M.D.

John D. Monteith

John D. Monteith: Fever Dream

Born in New Jersey in 1966, John D. Monteith is a self-taught artist currently living in Columbia, South Carolina. Working for more than 30 years now, he has been shown in many solo and group shows. His pieces have also been included in numerous public and private collections as well as a host of publications and periodicals.

Although his current focus is painting, the last three decades of production have been experimental in nature, exploring a wide variety of media and techniques. Whether it is collages assembled from old, found school yearbooks, wash drawings of chatroom avatars done in tobacco juice, or an installation of 30 digital frames (each displaying a slide show of hundreds of early dial-up era webcam selfies) his work has always delved into questions of otherness and the idea of parallel or shadow states of existence.

A life-altering event in 2020 moved Monteith toward his recent body of flat, intimately scaled, and deliberately muted or blurry paintings. Gleaned from re-photographed film stills or images he has either found or taken himself, he sees his new pieces as meditations on a certain amorphous, apparitional characteristic that has not only become a major component of his own, new reality but also part of what he senses to be an underlying feature of living in the 21st century. Hinting at a constant, subtle entropy with elements of dark humor, absurdism, and melodrama and painted using a subdued palette, his new, small paintings can be seen as the looking glass that many of us may already be on the other side of.

Luboš Plný

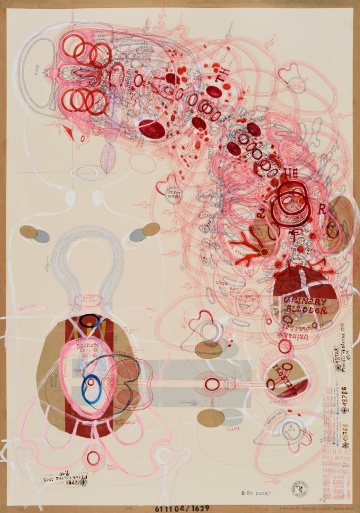

Luboš Plný: Transcendent Anatomy

Ricco/Maresca Gallery is pleased to announce an exciting new association with Christian Berst Gallery in Paris. This online exhibition is the first of a series of projects, both digital and in-person.

Luboš Plný was born in 1961 in the Czech Republic. From an early age, he had two passions: drawing and anatomy.

Plný began making art in the early 2000s. His works are codified examinations of the body, of that which animates and runs through it, as well as what threatens its deterioration. Lines and segments, resembling topographic surveys, are marked with numbers. These numbers do not indicate coordinates or altitudes, but rather the moment and duration of when each part of the artwork was created. This almost liturgical relationship with time is perfectly illustrated by the two numbers that invariably border the drawing, indicating the artist's age (in days), when he began the process of the artwork, and the age he reached upon its completion. This serves as a final acceptance of his own conclusion, a memento mori where sophistication contends with melancholy.

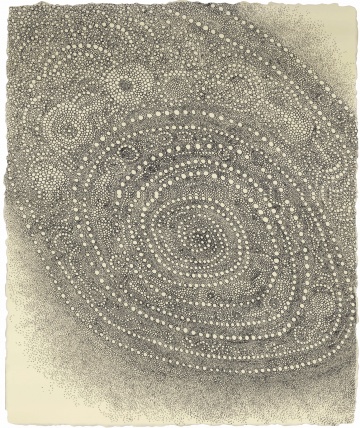

Hiroyuki Doi

Hiroyuki Doi: Infinity Clusters

Born in 1946 in Nagoya, Japan, Hiroyuki Doi, a former chef, started making art in the 1980s after the death of his younger brother from a brain tumor. What originated as a therapeutic requiem, has since become a mysterious, self-renewing act of abstract mapping that can be recontextualized in multiple ways.

Doi’s practice—which he describes as each piece evolving spontaneously until it finds its form—is very much akin to improvisational music, taking off from a few basic riffs to be created as it happens.

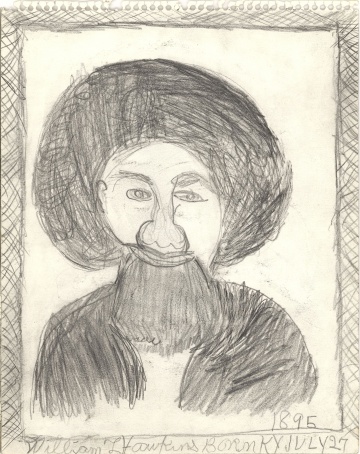

William Hawkins

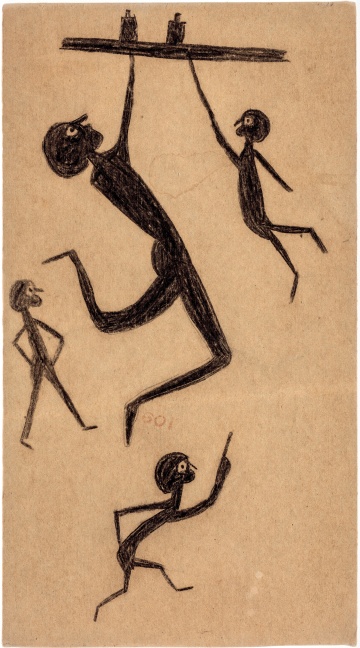

William Hawkins: Drawings

William Hawkins’s main source of inspiration was the print media of his time, the pictures in newspapers and magazines that he retrieved from the trash stored in a suitcase.

Before starting to work on a painting, Hawkins would often work out basic compositional problems on paper. The drawings presented in this online exhibition were always meant to be the beginning of a process that was wonderfully spontaneous. When asked about art-making, the first thing the artist would say was that he had been drawing all his life. This was true. Even though he did not start painting in earnest until the late 1970s (he was always a hard, industrious worker and never had the luxury of time), drawing could be done anywhere, quickly.

It was never Hawkins's intention to sell his drawings, so he didn’t treat them with particular care—he might have been working on one while eating lunch or dinner. There is nothing "precious" about the artist's work, and this extends to his drawings. It’s also true that they are as fearless and whimsical as his paintings are.

Kate Berry Brown

Kate Berry Brown: Clarity

Kate Berry Brown was born in 1978 and grew up in Evanston, Illinois. Her current body of work consists of meticulously carved wood and paper sculptures, which evolved from abstract ink drawings on cut paper and the desire to give them dimensionality.

The artist's woodworking journey began three years ago on a tiny island off the coast of Massachusetts called Cuttyhunk. "There’s no way of coming away unchanged from living such a simple island life; walking under vast skies every day for an entire season, completely surrounded by the ocean, collecting stones and moon shells,” says Brown. “The drawings I was mounting on the wood available to me were replaced by plain white paper; the softness of the paper wrapping around the wood curves—the hush of each piece—became my new inspiration."

Tricia Cline

Tricia Cline: The Life of an Image

Tricia Cline was born in Sacramento, California, in 1956. As a self-taught sculptor, she has been working for over 25 years from direct observation of female and animal forms. Her small, highly detailed porcelain clay sculptures are metaphors describing humans’ relationship to animals and to themselves as… animals. Cline’s method of observation without mental interpretation is influenced by the writings of psychologist James Hillman, who in his book Blue Fire describes a dream featuring a great black snake. Interpreting the meaning of the snake upon awakening (or restricting the vast unknown to what is known) will kill the image, cutting off any path to a transcendent reality.

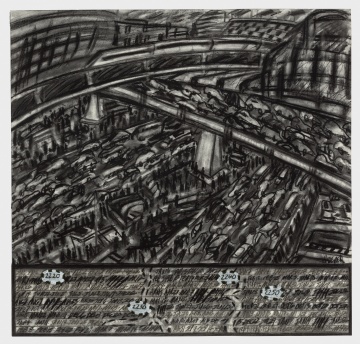

George Widener

George Widener: Mindscapes

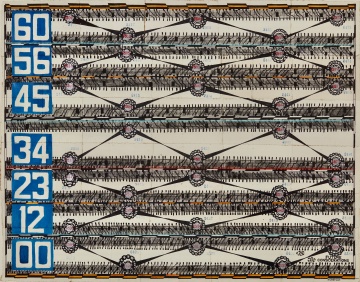

George Widener was born in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1962. A calendar savant, Widener has created distinct bodies of work that represent the depth and versatility of his visual and conceptual toolbox: from his Titanic works and Megalopolises to his Crispr and Pi works, from his Magic Circles and Magic Squares to his Self-Portrait series.

The group of works included in Mindscapes presents a series of expressive vignettes capturing the traffic and chaos of modern cities, which Widener experienced during past travels to Europe and Asia. Using his innate eidetic memory—the ability to recall an image from memory with great precision—Widener conjures these scenes with ink and charcoal, employing densely rendered and overlapping networks of lines. The small format of these drawings allows the artist to work quickly and spontaneously; the recurring date panels at the bottom of each work capture a unique aspect of his interior life—counting dates to calm himself down amid the urban turmoil.

Widener’s work is in private and museum collections worldwide, including the American Folk Art Museum in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art in Chicago, the Kroller-Muller Museum in the Netherlands, the Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland, the abcd/ ART BRUT collection and the Centre Pompidou, both in Paris.

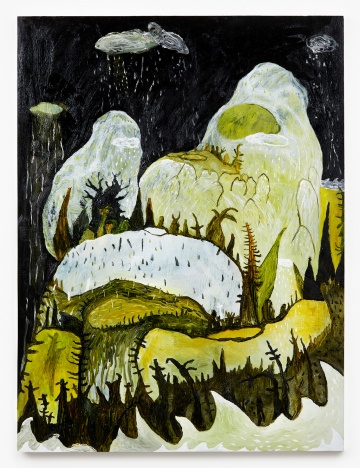

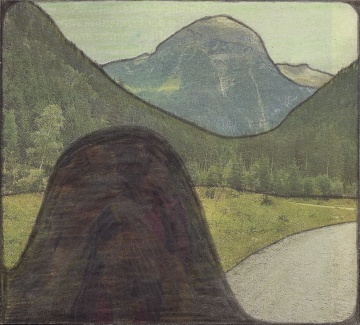

Mark Laver

Mark Laver: A Wild Silence

[Artist Debut] Laver was born in 1970 in Victoria, British Columbia and raised in a rural area of Vancouver Island, where he spent his childhood exploring the surrounding beaches, tidal swamps, creeks, and forests.

His current and ongoing body of work depicts landscapes of a mysterious beauty that is at once luscious and moody, cohesive and in flux. Without reference to photographs, drawings, real places, or even conscious memories, Laver starts with a limited palette and no pre-existing plans, and discovers his paintings in the act of painting, arriving at the composition last. Each work provides its own surprises, as new symbols and motifs emerge, grow, and repeat, adding to his ever-expanding invented world.

William E. Doleman

William E. Doleman: Utopia

William Eugene Doleman was born in San Francisco in 1949.

Since 1991, he has been living on and off in Grass Valley, California, a small mining town in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountain range. A self-described “volunteer peasant” and an eccentric, Doleman has lived in and out of a trailer for 50 years. “My parents went through the Depression when they were young teens,” he says. “That had an effect on me… They were very frugal, they lived off very little,” adding that he is planning on fixing up a motor home that he recently purchased—which will put him on his way to becoming a true nomad.

When he moved to California, Doleman started to tie-dye fabrics, and at one point it occurred to him to cut and stretch them to utilize as canvases. This pre-existing color base serves as inspiration for the drawings that then emerge: whirlpools of figures with varying degrees of human and animal traits that coexist happily in a flexible non-perspectival space—which Doleman manipulates by removing some of the color (or un-dying) to create negative spaces, luminosity, and contrast.

Thomas Lyon Mills

Thomas Lyon Mills: New Work

For over 30 years, Thomas Lyon Mills has been the only non-archeologist with permission to explore and paint alone in the Italian catacombs. Mills has also received unique access to paint in Mithraeums, in the temple ruins of the unknown civilization at Gabii, in Etruscan tombs down hill-sides hidden in forests, and up in a mountainous Paleolithic cave. With his on-site work and the influence of his dreams, he returns to his studio to work on pieces often for years.

Domingo Guccione

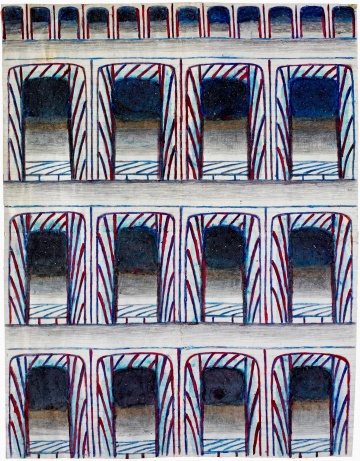

Domingo Guccione: Unseen Works

Guccione (1898 - 1966) worked in private and claimed to be channeling a mysterious force that took a hold of him in bouts of creative energy—when his body and mind were not his own. His oeuvre is both deeply abstract and reminiscent of futuristic architectural landscapes; of buildings and labyrinths that fluctuate between flatness and three-dimensionality, interweaving densely packed color with subtle shading.

All the works in this online exhibition have never been seen or offered.

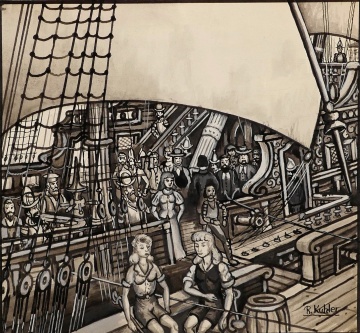

Renaldo Kuhler

Stories From Rocaterrania - Part II

Renaldo Kuhler (1931 - 2013) created an imaginary country he called Rocaterrania as a teenager and set out to illustrate its history for the rest of his life. An amalgam of Kuhler’s varied cultural and aesthetic tastes, Rocaterrania is a sovereign nation situated on the border of New York state and Canada, Rocaterrania’s name was derived from Rockland County, NY, Kuhler’s childhood home. The country has a unique government, military, language, religion, architecture, movie industry, and a fully mapped geography of cities, mountains, farmlands, lakes, and rivers. It also has a dramatic history of oppression, revolutions, prosperity, and reversals of fortune—one that mirrors the narrative arc of Kuhler’s own life.

This two-part exhibition features works

that have never before been offered.

Renaldo Kuhler

Stories From Rocaterrania - Part I

Renaldo Kuhler (1931 - 2013) created an imaginary country he called Rocaterrania as a teenager and set out to illustrate its history for the rest of his life. An amalgam of Kuhler’s varied cultural and aesthetic tastes, Rocaterrania is a sovereign nation situated on the border of New York state and Canada, Rocaterrania’s name was derived from Rockland County, NY, Kuhler’s childhood home. The country has a unique government, military, language, religion, architecture, movie industry, and a fully mapped geography of cities, mountains, farmlands, lakes, and rivers. It also has a dramatic history of oppression, revolutions, prosperity, and reversals of fortune—one that mirrors the narrative arc of Kuhler’s own life.

This two-part exhibition features works

that have never before been offered.

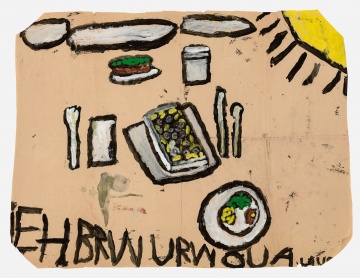

Laura Craig McNellis

Laura Craig McNellis: Here Comes the Sun

Laura Craig McNellis was born in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1957. As the youngest of four sisters. McNellis’s developmental disability became apparent early in her life. Because McNellis is non-literate and her speech understood only by family members, her paintings have become an extraordinary means of personal expression. Often a painting portrays an episode from her day and sometimes a series of works will develop from a particular event that fascinated her. Her acute powers of observation enable her to depict eloquently the people, objects, and events she encounters. Her art makes it clear that the artist sees a different, though in no way diminished, world.

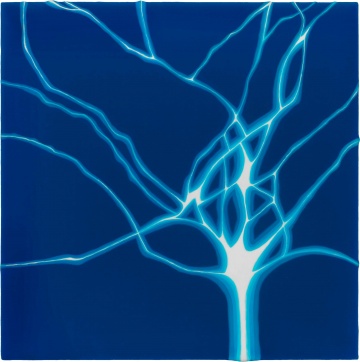

Hester Simpson

Hester Simpson: Paintings

Simpson's acrylic paintings layer color on color until their surface resembles a waxy patina. The artist's translucent fields hold geometric and organic systems of repetition that self-destruct and re-invent themselves, veering on and off the grid in a deceptively vast space.

Helmut Hladisch

Helmut Hladisch: Absence of Color

Hladisch (b. 1961) has been one of the eight residents of the Gugging House of Artists in the outskirts of Vienna since 2013. Using short, close-set strokes to fill in traced contours, Hladisch depicts everyday objects from memory or inspired by print media. His stylized drawings marry emotional intensity, imagination, ingenuity, and technical precision—crossing seamlessly into the modern and contemporary arenas.

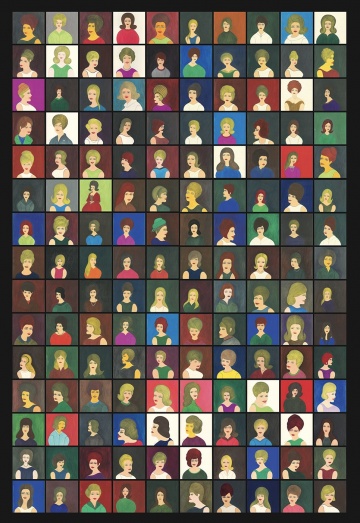

Nelson Patrick Viola

N.P. Viola's Newspaper Girls

September 19, 2024 - October 26, 2024

Ricco/Maresca is pleased to present an exhibition comprising more than 170 vibrant works on paper left behind by the previously unknown artist Nelson Patrick Viola. These works, which have never been exhibited and are collectively named Newspaper Girls, invariably depict women with bold lines and intense color blocks. Information handed down from one custodian of the oeuvre to the next indicates that Viola scoured newspapers to collect photographs of women, which he then used as the basis for each of his portraits. Every work is unique in its individuality, yet undoubtedly part of one artist’s vision. All the drawings were made in 14 x 17-inch spiral sketchbooks, sometimes signed and dated—with all the dates falling between the early and mid-1960s.

The son of two Italian immigrants, Viola was born in November 1910 in Bridgeport, Connecticut. He spent most of his young adult life working for a construction company at New York City’s Grand Central Terminal—until 1940, when he was drafted into the United States Armed Forces at the onset of history’s deadliest war. Viola was a Technician Fifth Grade soldier; he was not trained for combat but was recognized for his “specialized skills” in construction. Though the duration of Viola’s service is unknown, he survived the war and spent the remainder of his life working as a salesman in an auto shop. Not much is known about Viola’s personal life aside from a few basic facts: he spent the entirety of his life in Connecticut, married twice, had children with both wives, and lived to the age of 98.

The contrast between the bold expressiveness of Viola’s portraits and the stark obscurity of his life reveals the private world of an image collector fascinated with femininity, youth, and the presentation of self. It also highlights the mysterious process through which a self-taught artist transformed the popular culture and aesthetic sensibilities of his time into art created for his own pleasure.

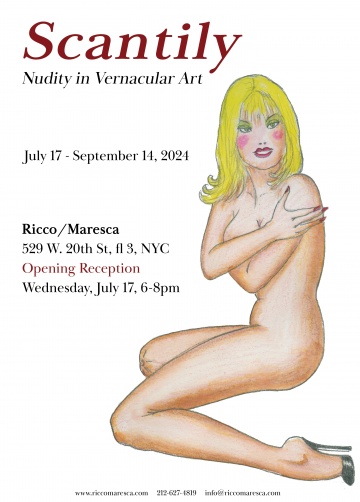

Scantily: Nudity in Vernacular Art

July 17, 2024 - September 12, 2024

The history of the nude runs as far back as art itself. The human nude is the ultimate universal subject—timeless, possessed by all, and yet highly individual and subjective. When it comes to public reception, nudity is divisive at best; from a celebration of the body to the ultimate scandal, no singular person or culture can ever fully agree on just how to display or conceal the bare body. In traditional artistic training, the nude has long been regarded as an essential educational tool, and it’s rare to encounter an academic program that does not insist upon an artist’s understanding of human anatomy. However, where this objective is widely considered as educational, the boundaries between the nude body as artistic, pornographic, and informative are incredibly hazy.

Scantily presents depictions of the nude or partially nude form, as conceived mostly by vernacular, self-taught artists, both known and anonymous. In the art created on the margins of the academy, the human body stands unfiltered by the lens of academia and is instead the full product of the artist’s experience.

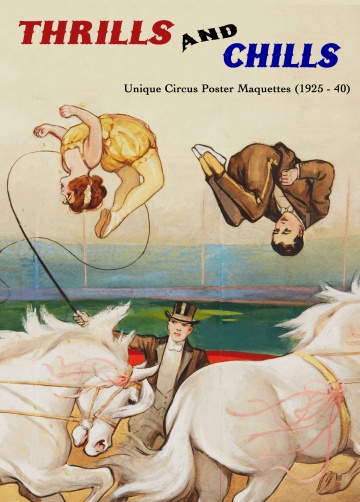

Thrills and Chills: Unique Circus Maquettes (1925 - 40)

July 17, 2024 - September 12, 2024

The American circus, which had its golden age in the late nineteenth through the mid-twentieth century, was known for all things bold and daring. From acrobats to clowns, tightrope walkers to jugglers to musicians, the circus had something in it for everyone. A notable identifier of the American circus’ golden age lies in its promotional materials, with the sensational illustrations and bold typeface of their classic poster designs. Thrills and Chills, features a dynamic grouping of these one-of-a-kind maquettes, made by anonymous illustrators between 1925 and 1940, which put on full view the unique blending of advertisement and the deep artistic potential within the world of classic circus posters.

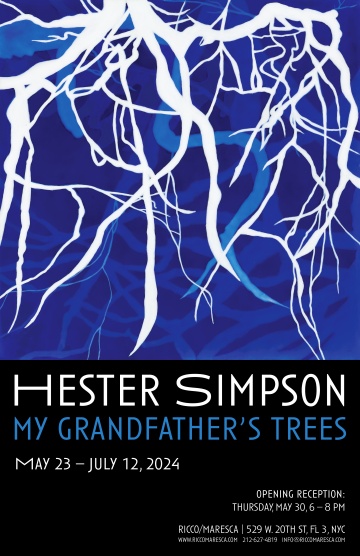

Hester Simpson

Hester Simpson: My Grandfather's Trees

May 23, 2024 - July 12, 2024

Hester Simpson was born in 1949 on Long Island and raised in the town of Locust Valley, where she spent her childhood in the company of her French grandparents, Ida and Jean Schweckler. Steeped in their language, their customs, their frugality, optimism, and love of nature, she developed an early affection for their way of life. Her grandfather, a painter, included her in his many activities in and around the studio. In their War World II Victory Garden, under an enormous apple tree, they gathered beets and rhubarb to boil down into a personal brand of alizarin crimson. Jean Schweckler’s paintings hung throughout the house from both walls and ceilings. The dining room, a mural of rubber-making in Brazil, covered the walls, replete with exotic flora and fauna, cerulean skies, trees and streams. Friends and neighbors regularly gathered for impromptu conversation and a glass of wine.

Today, decades after his passing, Simpson credits her grandfather's spirit with her own passion for her painting practice. My Grandfather’s Trees honors the profound connection she maintains with her childhood in Locust Valley. In the wake of her mother’s passing, she walks through Central Park to her studio and the trees “speak” to her. She snaps a photo, and for the first time uses photography to enlist their exact form as an expression of her present grief, as well as an homage to life. Trees, it seems, contain souls within; her family hidden in plain sight, here and now. Moving from her previous geometric abstraction, Simpson now employs a new vocabulary of arboreal forms. She works slowly and deliberately, layering intense color in acrylic paint, alternating between pouring and brushing, a technique she developed in the late 1990s. The result is an examination of biomorphic pattern with a nod to the preternatural, a quality that both reflects and affirms her premise of regeneration.

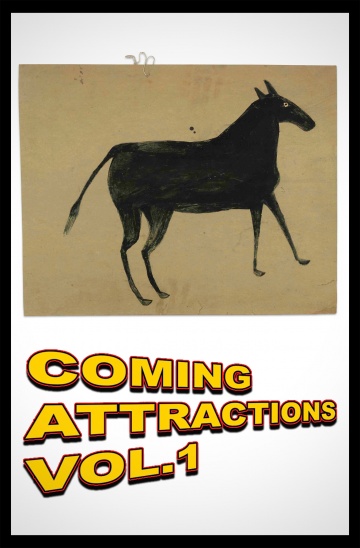

Coming Attractions Vol. 1

May 23, 2024 - July 12, 2024

Ricco/Maresca is pleased to introduce Coming Attractions, a series of exhibitions that will take place periodically in our Gallery Two space. The term "coming attractions" is particular to an era in American cinema (roughly between 1940 and 1980) when going to the movies was a major social activity. These previews were typically shown before the main feature at a movie screening and served to advertise upcoming films. The concept played a key role in the cinema experience, building anticipation and excitement among the audience. The style of these trailers has evolved over time, but in the mid-20th century, they often had a very direct and exuberant flair, with voiceovers that were emphatic and persuasive, using phrases like: "Don’t miss," "Coming soon," or "In this theater."

Coming Attractions, in the context of Ricco/Maresca, aims to capture the thrill of discovery that has historically been part of the gallery’s spirit. It will always present dissimilar works selected for their quality and freshness of expression. Vol. 1 presents a powerful “abstract blocks” variation quilt from Tennessee backed with feed sacks (ca. 1930-40), as well as a “hired man” sized quilt made with pieced fabrics and thread ties, a masterpiece of textile art (ca. 1920-30)—both quilts likely African American. Also included is a sophisticated mule drawing by Bill Traylor (1853 -1949), a contemplative scribe (likely a self-portrait) by Martín Ramírez (1895–1963), and a unique voting booth curtain (ca. 1920-30) made with canvas painted with stripes in the colors of the American flag, and stenciled: “MILLER AND DAVIS CO. MINNEAPOLIS, MINN. DISTRIBUTORS IN MINNESOTA FOR DOUGLAS COLLAPSIBLE VOTING BOOTH. MADE IN CRETE, NEBR.” Coming Attractions Vol. 1 also presents a selection of boldly lined, color-blocked portraits of women created by an obscure self-taught artist named Nelson Patrick Viola (1910 – 2008). Viola, who worked for a construction company in New York City’s Grand Central Terminal and served in World War II, left behind 200+ vibrant portraits of women inspired by newspaper photographs from the 1960s. The exhibition concludes with two anonymous SX-70 polaroid self-portraits, created in the 1970s, of a crossdresser enamored with their legs—130 of which were found in an abandoned self-storage unit in Massachusetts.

Jorge Alberto Cadi, Le Fétichiste, Miroslav Tichý

Fetish

April 18, 2024 - May 18, 2024

Fetish

Photographs by Jorge Alberto Cadi, Le Fétichiste, and Miroslav Tichý

In partnership with christian berst art brut

This exhibition showcases three bodies of work exploring the connections between

vernacular photography, voyeurism, appropriation, and the metamorphosis of desire into

image-making.

Miroslav Tichý (1926 - 2011) was known for his unique approach to photography,

characterized by clandestine images of women and girls in his hometown of Kyjov, Czech

Republic. Following a tumultuous period that included military service and a potential

breakdown, Tichý withdrew from society, becoming a recluse. In the 1950s, he turned to

photography as a form of non-political expression in response to the communist regime's

social constraints. His handmade cameras, constructed from rudimentary materials like

cardboard, enabled him to capture candid moments swiftly and discreetly, imbuing his

images with an unposed, rebellious aura.

In the bustling streets of Havana, Jorge Alberto Cadi (b. 1963) is affectionately known

as "El Buzo" ("The Diver"). Cadi, who grapples with schizophrenia, is on a relentless quest for

artistic inspiration amidst the city's discarded relics—transforming found black and

white photographs into otherworldly works. Faces are altered with eerie features, distorted

and even erased—only to resurface hauntingly elsewhere in the composition. For the artist,

these anonymous photographs from bygone eras are poignant reminders of emigration,

departures, farewells, and the myriad separations that have left an indelible mark on his

homeland.

Created between 1996 and 2006, the collection of amateur prints by an unknown

photographer (who we refer to as Le Fétichiste) captures images of legs clad in stockings—

snapped on the streets or gleaned from a television screen. In its essence, the creator’s

pursuit echoes that of Tichý, with a notable distinction: here, the photographer occasionally

steps into the frame as a subject. Both instances—typical of art brut—invite us to question

how our perceptions are shaped and the ways in which individual mythologies infuse the

collective imagination.

An Outsider's Eye

April 18, 2024 - May 18, 2024

DISCOVERIES FROM BRUCE SILVERSTEIN GALLERY, CURATED BY FRANK MARESCA

Every art exhibition tells a story, one outlined by the curator's choices and enriched over time by the viewers. In this case, the initial premise is elegantly simple and stated in the title itself, but the true beginning is found in life, not in art; in the lifelong relationship between two people whose personal histories and visual sensibilities led them on distinct yet intersecting paths.

Frank Maresca and Bruce Silverstein have been in each other's orbit for more than 50 years. Between the late 1960s through the early 2000s Frank (whose first career was in fashion and beauty advertising photography) shared a working studio space with Bruce's parents, the photographer Larry Silver and his wife and representative Gloria. Now gallery neighbors on the same floor, still friends after all these years, Frank and Bruce maintain an ongoing dialog that led to this exhibition. Their taste is sometimes different, but they are both drawn to the concept of crossover-between self-taught and mainstream art or as a dialogue across art forms-and interested in finding lesser-known precursors to widely embraced trends. As art dealers who were collectors first, they lead with intuition and instinct.

Both Ricco/Maresca and Bruce Silverstein Gallery chose to focus on developing fields that are constantly in flux. It's now widely recognized that the emergence of art brut and self-taught art stemmed from the avant-garde movements of the first half of the 20th century, which in their uprising turned the attention to forms of creativity that were not bound by the stronghold of the academy. Photography, then an emerging art form, became an integral part of this experimental ethos. In the last few decades, both non-academic art and photography, have had to wage the battle of being fully recognized as fine art, not its odd cousins, and find their place in significant collections and museums.

An Outsider's Eye features more than 20 artists, including Karl Blossfeldt, Edward Weston, Man Ray, André Kertész, Dorothea Lange, Paul Outerbridge, Lisette Model, Walker Evans, Aaron Siskind, Bill Cunningham, and Francesca Woodman, among others. Works by these artists, discovered anew in the context of this exhibition, bring Frank and Bruce's intertwined journeys full circle. Frank's selection explores a wide range of themes and styles, encompassing the human figure and still life, as well as documentary photography and abstraction. His aim was to juxtapose raw vs. elegant elements: the unembellished beauty of anonymous snapshots he collected over many years with the flawless compositions of masters, which he sought to emulate in his own photographic work. This exhibition also unites Frank and Bruce's enduring awareness of works of art not solely as images or forms, but as tangible objects whose surface and patina bear the marks of their journey through time.

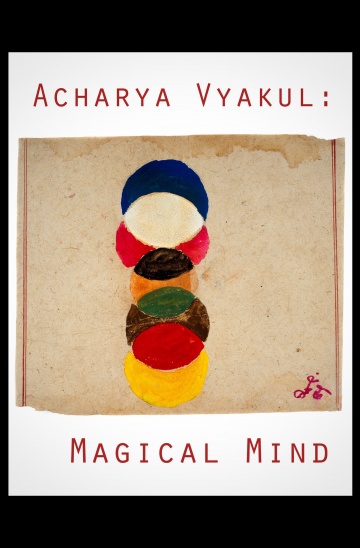

Acharya Vyakul

Acharya Vyakul: Magical Mind

March 1, 2024 - April 13, 2024

Acharya Vyakul (1930 – 2000), whose full name was Acharya Ram Charan Sharma, lived most of his life in Jaipur, the capital of India’s Rajasthan. He was member of the Brahman caste within Hindu society. Brahmans are designated as the priestly class, serving as ministers and spiritual teachers. The basis of the age-old veneration of Brahmans is the belief that they are inherently of greater ritual purity than members of other castes and that they alone can perform certain vital religious tasks. The study and recitation of the sacred scriptures was traditionally reserved for this spiritual elite, and for centuries all Indian scholarship was in their hands.

Vyakul was a guru to many and an ardent collector of magical and religious items, establishing his own private museum in Jaipur with a collection of folk and Tantric art. He was also a prolific artist, poet, and philosopher who painted Tantric iconography with fluid improvisational strokes. He used a wide range of materials—from coal, flowers, stone pigments, and marker pens to communicate a mystical vision with dynamic energy. He referred to himself as a “modern artist with roots" and exhibited worldwide, including in the exhibition "Magiciens de la Terre" at The Centre Pompidou in Paris in 1989.

All the works in this exhibition are from the collection of The William Louis-Dreyfus Foundation. Established in 2013, The Foundation is dedicated to the mission of educating the public about the importance of art and increasing public awareness of self-taught and emerging artists. In 2015, the Foundation announced its intention to donate proceeds to the Harlem Children's Zone when it sells works from its collection. As part of the Foundation's broader philanthropic mission, proceeds from the sales of its artworks will benefit the Harlem Children's Zone as well as the Foundation itself.

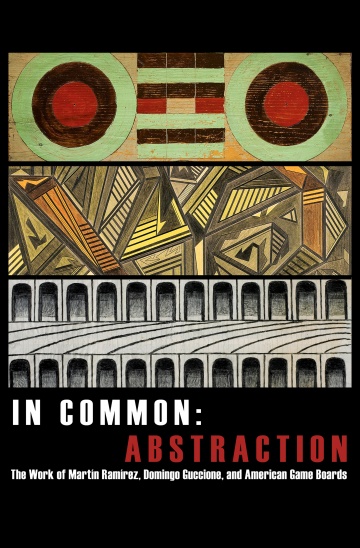

Martín Ramírez, Domingo Guccione

In Common: Abstraction. The Work of Martín Ramírez, Domingo Guccione, and American Game Boards

March 1, 2024 - April 13, 2024

This exhibition features the drawings of Martín Ramírez (Mexican, 1895 – 1963) and the geometric abstract work of Domingo Guccione (Argentinian, 1898 – 1966) juxtaposed with vintage American game boards—created by unknown artists between the late 19th century and the first half of the 20th century. Through the dialogue between these parallel visions—originating in radically different contexts—we consider the visual language of abstraction as a bridge between self-taught, vernacular, and modern art.

MARTÍN RAMÍREZ (1895 – 1963)

Martín Ramírez was born in Jalisco, Mexico, and is widely known as one of the preeminent self-taught masters of the 20th century. Thrust by political and religious upheavals caused by the Mexican Revolution and seeking to support his family, Ramírez relocated to the United States in 1925. He worked as an impoverished immigrant in the California mines and railroads until he was picked up by police in 1931—reportedly in a disoriented state. Ramírez was eventually declared schizophrenic (with previous diagnoses of manic-depression and catatonic dementia praecox). He was committed first at Stockton State Hospital and then at the DeWitt State Hospital in Auburn, where he spent the rest of his life. It was there where he discovered art and created the complex and compelling drawings for which he is known.

Over the course of his life, Ramírez produced around 500 works. The imagery is often reminiscent of his own life experiences: Mexican Madonnas, animals, cowboys, trains, and landscapes merge with scenes of American culture and create a profound documentation of a Mexican living and working in the United States. Compositionally, he renders space into multi-dimensional layouts, often using rhythmic repetition and gentle shading. Later in his life, he incorporated collage into his works, adding newspaper clippings and previous drawings for depth and texture.

Ramírez’s technical skill, stylistic evolution, and thematic coherence led Roberta Smith of the New York Times to call him “simply one of the greatest artists of the 20th century.” In 2015, the United States Postal Service released a set of 5 commemorative “Martin Ramirez” Forever stamps, which marked the first time that an “outsider” artist and a Mexican immigrant was featured on a USPS Stamp.

DOMINGO GUCCIONE (1898 – 1966)

Domingo Guccone was born in Buenos Aires to Italian parents. He was a trained classical musician, working as a concert guitarist and instructor to many students, but was never exposed to visual art—and in fact suffered from color blindness. He drew mostly in private and claimed to be channeling a mysterious force that took a hold of him in bouts of creative energy—where his body and mind were not his own. Accordingly, Guccione could (or would) not explain his finished works and in turn ask viewers what they saw in them.

Guccione did not sketch his drawings, working quickly and with a minimal range of materials; thick sheets of paper, graphite, colored pencils, and a straight piece of wood, about 4” long, with no measurement markings. The 222 works that he left behind, which were produced between 1930 and 1955, are compact kaleidoscopic arrangements where geometric patterns intertwine with irregular linear shapes. They are both deeply abstract and reminiscent of futuristic architectural landscapes; of buildings and labyrinths that fluctuate between flatness and three-dimensionality, interweaving densely packed color with subtle shadings.

Guccione's work had never been seen outside of his immediate family until his debut with Ricco/Maresca at the Independent Art Fair in New York (March 2020).

VINTAGE AMERICAN GAME BOARDS

LATE 19TH CENTURY - FIRST HALF OF THE 20TH CENTURY

Created between the late 19th century and the first half of the 20th century as functional objects by unknown artists, American game boards transcend their original utilitarian purpose and stand on their own as cousins of modern art. This exhibition presents examples of parcheesi, checkers, and Chinese checkers, decontextualizing these works to highlight their concrete beauty, while acknowledging the mystery and gravitas that they possess as objects that once participated in everyday life.

In the 19th century, most game boards were homemade for personal use or produced in domestic workshops for sale within the immediate community—much in the same way as bird decoys, dolls, and quilts. Artists used the materials at hand; easily accessible, generally native hardwoods and standard oil-based household paint—whose durability could withstand the continuous quiet abrasion of the moving parts on the surface.

In the informal environment of a young American nation, artists transformed pre-established patterns into personal compositions, taking creative liberties analogous to jazz—if we think about the framework of the game as a basic melody and of each artist’s visual execution as a kind of musical improvisation. In the best of cases, game boards embody this powerful junction of familiar and new information; of tradition and innovation, with the latter manifesting itself through various degrees of abstraction, deconstruction, and formal embellishment or distillation.

Jung Eun Hye

Jung Eun Hye: My Dog, Jiro

December 14, 2023 - February 17, 2024

Born with Down syndrome in 1990, Jung Eun Hye’s artistic talent was recognized and encouraged at an early age by her parents. In 2020 the screenwriter Noh Hee Kyung attended a solo exhibition featuring Jung’s work and met the artist. This encounter inspired Noh to create a role for Jung in the Korean drama Our Blues, which premiered in 2022. Jung excelled in her role as the twin of a woman who is conflicted by her sister’s developmental disability and quickly became a household name.

In the fine art arena, Jung’s work has been shown in numerous solo and group shows. My Dog, Jiro, her first exhibition in New York, focuses on the artist’s sophisticated representations of her beloved pet—a compelling chapter of her broad interest in portraiture.

Jiro, both vigilant and gentle, is always present in Jung’s studio. The artist rescued him from the streets on a rainy day nine years ago. In their bond, and through art making, she has carved yet another avenue of communication with a world that has always deemed her an outsider.

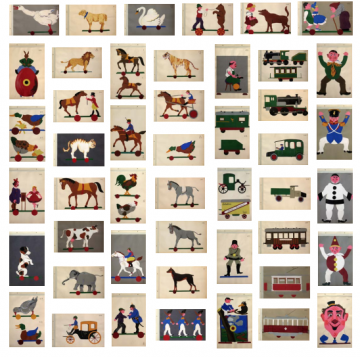

Unknown Artist

Toy Stories: Vintage Toy Illustrations

December 14, 2023 - February 17, 2024

This extraordinary collection of vintage toy illustrations, produced by a single artist whose name is unknown, transcends its original commercial purpose and relates to the modern art movements that emerged about two decades after it was produced—particularly Pop Art.

Blurring the boundaries between graphic and fine art, these playful and iconic works are symbols of a simpler time; one when all toys were analog. They remind the viewer of the visual lexicon of fairy tales; its archetypal motifs; its pure and condensed sense of fantasy. With this comes the invitation to invent new stories and rediscover a sense of play that is getting lost in the digital world.

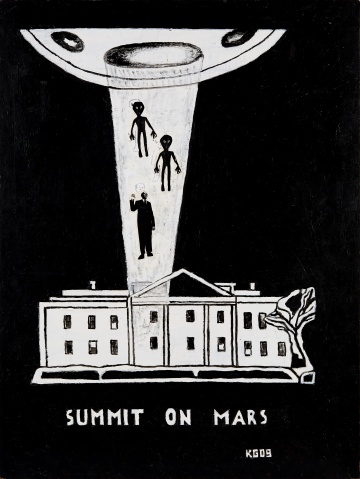

Ken Grimes

Ken Grimes: Evidence for Contact

October 26, 2023 - December 2, 2023

Ricco/Maresca is pleased to present "Evidence for Contact," a retrospective exhibition organized on the occasion of the release of a major book by the same title. Published by Anthology Editions, this volume is entirely devoted to the life and 40-year career of Ken Grimes.

Sewn Together: The Converging Worlds of Southern American Quilts and Boro Textiles

September 14, 2023 - October 21, 2023

Southern American quilts and their distant cousins, Japanese Boro textiles, have distinct origins, histories, and cultural contexts, but they share some commonalities in terms of their historical significance and artistic expression. Together, they offer fascinating insights into the power of textile art and storytelling.

Leopold Strobl

Leopold Strobl: Views

September 14, 2023 - October 21, 2023

Strobl was born in Mistelbach, Lower Austria in 1960. He has devoted himself exclusively to art for almost 40 years, and has been a guest of the Open Studio program at the Gugging Art Brut center in the outskirts of Vienna for more than 16 years. He draws in the morning and single-mindedly finishes a new work in one sitting. Strobl's works are generally no bigger than a few inches on the longest side and can be almost as small as a postage stamp; they come to the artist as little visual epiphanies and strike the viewer with this poetic immediacy.

Bill Traylor

Bill Traylor: Plain Sight

April 27, 2023 - June 3, 2023

Ricco/Maresca’s history with Bill Traylor is almost as long as the gallery’s history itself. Our book "Bill Traylor: His Art, His Life," the first volume devoted to the artist, was published by Alfred A. Knopf in 1991. Since then, we have mounted three one-person Traylor shows (in our Hudson Street, Wooster Street, and Chelsea spaces respectively), sold the first Traylor work acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, built William Louis-Dreyfus’s Traylor collection (the best ever assembled), and published the catalog "Bill Traylor: Observing Life" (1997).

It is now our privilege to present "Bill Traylor: Plain Sight." This exhibition is a touchstone in the gallery’s longstanding endeavor to earn the American self-taught master the recognition he has always deserved. "Bill Traylor: Plain Sight" follows more than 45 solo gallery and museum exhibitions, including the major retrospective "Between Worlds: The Art of Bill Traylor," curated by Leslie Umberger at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (2018)—whose eponymous book is the most comprehensive scholarly publication on the artist’s life and work. Our exhibition celebrates the posthumous upward trajectory of Traylor’s work, which in the early 1980s could be acquired for an average market value of $1,500, and in 2020 reached an auction record of $507,000 for "Man on White, Woman on Red / Man with Black."

Bob Gibson Tjungarrayi

Bob Gibson: His Father's Country

April 27, 2023 - June 3, 2023

Bob Gibson Tjungarrayi was born at Papunya in 1974, before moving with his family to the small community of Tjukurla during the Australian outstation movement of the 1980s. This was a time when many Ngaanyatjarra people moved from government outposts near to Alice Springs back into the Western Desert to be closer to their ancestral homelands. Gibson began painting at the Tjarlirli Art Centre in 2007, and quickly found a unique rhythm and approach to mark-making; his style is characterized by bold colors and an inimitable freedom of movement, expressing ancient stories with contemporary flair.

“Bob Gibson: His Father’s Country” is supported by D’Lan Contemporary

Unknown Artists

Formed with Function

March 3, 2023 - April 22, 2023

"Formed with Function" is conceived as a sequel to Ricco/Maresca’s show titled Chance (December 1991 - January 1992), which was an exploration of the found object as art—an interest of our gallery since the 1980s that continues to this day. In this show, my focus is not so much the classic objet trouvé—that which becomes art by chance—but objects that were created with a functional purpose in mind, and whose aesthetic qualities both enhance and transcend it.

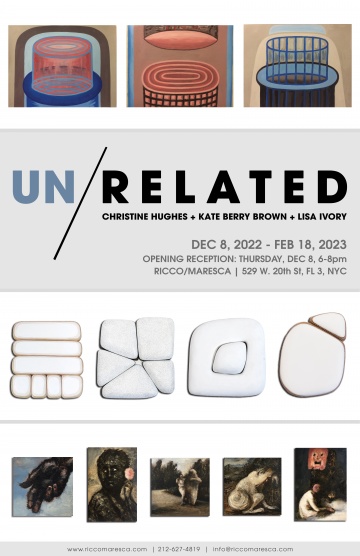

Christine Hughes, Kate Berry Brown, Lisa Ivory

Un/Related: Christine Hughes, Kate Berry Brown, Lisa Ivory

December 8, 2022 - February 18, 2023

Ricco/Maresca is pleased to present Un/Related, featuring the work of contemporary artists Christine Hughes, Kate Berry Brown, and Lisa Ivory. The exhibition imagines a visual narrative where the works presented, however dissimilar, illuminate each other in thought-provoking ways. From the iconic austerity and intelligent abstraction of Hughes’s enamel paintings on paper, to the sumptuous materiality and detailed construction of Brown’s carved wood wall sculptures, to the dream-like pull and atmospheric symbolism of Ivory’s oil paintings. Un/Related unfolds in a lucid, multi-layered exploration of form, space, color, and non-literal representation that culminates in three distinct visions.

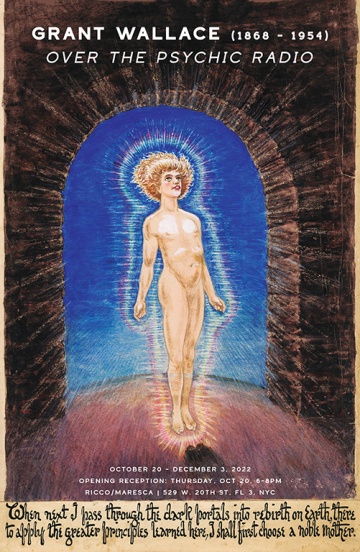

Grant Wallace (1868–1954)

Grant Wallace: Over the Psychic Radio

October 20, 2022 - December 3, 2022

Ricco/Maresca is excited to present the first gallery exhibition ever to be mounted of the work of Grant Wallace (1868–1954). "Over the Psychic Radio" features 31 works from a collection that was recently discovered by the artist’s great-grandchildren.

Only ten works by Wallace have been previously seen by the wider public. They were exhibited between 1997 and 1998 at the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore as part of "The End Is Near! Visions of Apocalypse, Millennium, and Utopia" and are illustrated in the eponymous catalog, published by Dilettante Press. The exhibition and publication were curated and authored by Roger Manley.

Grant Wallace was born in Hopkins, Missouri, in 1868, one of 9 children. He set out for New York City at age 19, where he studied and developed his interest in the occult. Wallace eventually made his way to California, where he worked as an editorial illustrator and reporter for the San Francisco Examiner and San Francisco Chronicle. He graduated to editorial writer for the Evening Bulletin and covered the Russo-Japanese War in 1904 among a group of war correspondents that included Jack London and Richard Harding Davis.

Just before World War I, Wallace settled with his family in Carmel, California, where he began experimenting with telepathy, or what he referred to as "mental radio.” Over the next two decades, he channeled his visions and messages into elaborate portraits, texts, and complex diagrams and calculations. Through his work, Wallace endeavored to prove reincarnation, extraterrestrial life, and the coexistence of the living with the dead.

Mark Laver

Mark Laver: Within

September 15, 2022 - October 15, 2022

Ricco/Maresca is pleased to present "Mark Laver: Within," the artist's first solo exhibition in New York City.

Laver was born in 1970 in Victoria, British Columbia and raised in a rural area of Vancouver Island, where he spent his childhood exploring the surrounding beaches, tidal swamps, creeks, and forests.

His current and ongoing body of work depicts landscapes of a mysterious beauty that is at once luscious and moody, cohesive and in flux. Without reference to photographs, drawings, real places, or even conscious memories, Laver starts with a limited palette and no pre-existing plans and discovers his paintings in the act of painting. Each work provides its own surprises, as new symbols and motifs emerge, grow, and repeat, adding to his ever-expanding invented world.

Most recently, Laver has retaken to a curved space technique that he started experimenting with in his twenties, opening increased formal and conceptual possibilities.

Paddy Bedford

Paddy Bedford: Ancestral Present

May 6, 2022 - June 18, 2022

Ricco/Maresca is excited to present the debut exhibition of the work of the Australian Indigenous master Paddy Bedford, the first solo show of the artist to take place in the United States.

Paddy Bedford (ca. 1922 - 2007) was born in the East Kimberley region of Western Australia, in a property that gave him his surname–Bedford Downs Station.

Like many of the indigenous men in the Kimberley, Bedford worked as a stockman, but was paid in rations. In 1969, when the law required equal pay for blacks and whites alike, station owners responded by laying off their indigenous workforce, including Bedford. He worked for a while on road building, but ended up forced on to welfare by injury.

Bedford was involved in painting as part of ceremony throughout his life, but he only began painting on canvas for exhibition after the establishment of the Jirrawun Aboriginal Art Corporation in 1997 (formed to assist the development and sale of works by Indigenous artists from parts of the Kimberley). In a remarkable career as a painter that spanned less than ten years, Bedford achieved great critical acclaim in Australia and abroad and has been recognized as one of Australia’s most important artists.

George Widener

George Widener: Count Down

March 4, 2022 - April 30, 2022

George Widener was born in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1962. Throughout his career, now spanning almost three decades, Widener has created distinct bodies of work that represent the depth and versatility of his visual and conceptual toolbox. Count Down presents a survey of work from diverse series: Megalopolis, Robot Teaching Games, Crispr, Maps, Magic Circles, Calendrical Computations, Cityscapes/Mindscapes, and Gambling/Probability—created between 2010 and 2022.

Widener’s work is in private and museum collections worldwide, including the American Folk Art Museum in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art in Chicago, the Hamburger Bahnhof Museum in Berlin, the Museum Gugging in Klosterneuburg, Austria, the Kroller-Muller Museum in the Netherlands, the Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland, the abcd/ ART BRUT collection and the Centre Pompidou, both in Paris.

Martín Ramírez

Martín Ramírez: Memory Portals

December 11, 2021 - February 26, 2022

A prolific draftsman, Martín Ramírez is considered one of the preeminent self-taught masters of the twentieth century. From ranch owner and agriculturist in Mexico, to miner and railroad worker in the United States, to patient and artist at two psychiatric hospitals in California—only in recent decades have we been able to appreciate the full complexity of Ramírez’s life. A quintessentially twentieth-century life that provided the source material for his sophisticated and enchanting compositions. Despite the hurdles Ramírez faced in his life—the economic instability following the Mexican Revolution, his migration to the United States, his self-imposed exile during the Cristero Rebellion, economic precarity during the Great Depression, and forced institutionalization in U.S. psychiatric hospitals—Ramírez was able to insist on creativity.

"Memory Portals" will focus on the artist's recurrent and mysterious depiction of arches, doorways, and portals—and their formal and symbolic significance across his oeuvre. The exhibition features a conversation between Brooke Davis Anderson, curator of the groundbreaking "Martín Ramírez" exhibition at the American Folk Art Museum (2007), and Juan Omar Rodriguez, Latinx curator of contemporary art and Curatorial Fellow at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

Domingo Guccione

Domingo Guccione: Spiritual Geometry

October 28, 2021 - December 4, 2021

Domingo Guccione was born in Buenos Aires in 1898, he was a mystic, a classical musician, and a self-taught artist. The body of work that he left behind, produced between 1930 and 1955, is a compelling example of Latin American geometric abstraction.

Guccione worked in private and claimed to be channeling a mysterious force that took a hold of him in bouts of creative energy; he did not sketch his drawings, working quickly and with a minimal range of materials. His geometric landscapes are reminiscent of futuristic buildings and labyrinths that interweave densely packed color with subtle shadings.

After Guccione's death in 1966, his oeuvre remained in his family’s possession (and unseen by a wider audience) until 2020—when Ricco/Maresca mounted his art world debut at the Independent Art Fair.

Spiritual Geometry, the artist's first one-person gallery exhibition, will present works that have never been seen or offered.

Johann Garber, Johann Hauser, Helmut Hladisch, Johann Korec, Alfred Neumayr, Günther Schützenhöfer, Leopold Strobl

GUGGING / ART BRUT

September 18, 2021 - October 23, 2021

We are pleased to announce gugging / art brut, featuring over 30 works by six artists, produced from the 1970s to the present at Gugging—Austria’s foremost cultural center dedicated to championing the field of art brut. Spanning across generations of artists who found their calling at Gugging, this exhibition highlights the profound originality and remarkable artistry that this forward-thinking institution has fostered for many decades. gugging / art brut is Ricco/Maresca’s second exhibition featuring artists of Gugging since their debut at the gallery in 2012.

Alice Hope, Bastienne Schmidt, Toni Ross

No W here: Alice Hope, Bastienne Schmidt, Toni Ross

June 3, 2021 - September 11, 2021

A few months before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, artists Hope, Schmidt, and Ross agreed to each select an artifact from the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s vast collection and respond to it creatively. In a serendipitous event, they all chose the Navigational Chart (Rebbilib) from the Marshall Islands.

No W here weaves the three individual responses resulting from this inquiry into one visual narrative that strives to facilitate recalibration and sense of place in this era of disequilibrium.

Artists Unknown

PLAY: American Game Boards 1880 - 1940

March 18, 2021 - May 20, 2021

Including parcheesi, backgammon, checkers, Chinese checkers, solitaire, and mills boards—all dating between the late 19th through the mid-20th century. Not created as modern or contemporary art, these game boards relate directly to (and often precede) works of geometric abstraction and minimalism.

George M. Silsbee

Explanatory Marks: The Mystical Drawings of George M. Silsbee (1840 - 1900)

January 28, 2021 - March 13, 2021

George M. Silsbee was a Civil War veteran with many occupations—artist, maker of daguerreotype images, organ builder, and miner among them. The details of his life are obscure, but we know that he was based in Colorado for twenty years toward the end of his life. Around 1891, Silsbee created what he would describe as his master oeuvre; a series of large works on paper backed with linen, densely rendered with writing, calligraphy, charts, and symbols revolving around freemasonry, mysticism, and the occult.

"Explanatory Marks" will present a collection of nine such works, which have never been seen until now.

Leopold Strobl

Leopold Strobl: ONE

October 29, 2020 - January 23, 2021

Strobl's second one-person exhibition after his debut in 2016. Presenting a selection of his most recent works--all produced between 2019 and 2020. Strobl, born and based in Austria, makes intimately scaled works on paper where naturalism and abstraction seamlessly converge.

C.T. McClusky

C.T. McClusky: Circus Surreal

September 17, 2020 - October 24, 2020

McClusky was a circus clown who spent the winter seasons between the late 1940s and mid-1950s at a boarding house in Oakland, California. Working with found materials, he completed 53 mixed media collages on cardboard incorporating photographic cutouts, illustrations, as well as ephemera such as chocolate and candy wrappers. His vignettes from circus life are candid, nostalgic, and strikingly surreal.

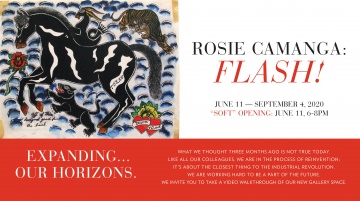

Rosie Camanga

Rosie Camanga: Flash!

June 11, 2020 - September 4, 2020

Camanga (1910-?) "moved to Honolulu from his native Philippines sometime prior to World War II ... After a couple of years, Rosie had drawn about 400 sheets of flash and left to open his own shop ... [He] was a complete original. Humorous and tough-minded, he survived for decades in control of his own game in a volatile honky-tonk environment ... [His flash] segued from standardized versions of classic tattoo designs to eccentric and mysterious scenarios that were his alone. The format of a sheet of flash, crowded with multiple images, or the notion that something might be appealing to someone to wear indelibly for life, were mere jumping-off points for the world he created. He often collaged sheets with images he liked, which he’d clipped from a magazine or assembled from previous designs, which regularly depicted things and sentiments never seen in any other tattoo context. He continued to draw after he stopped tattooing, using the flash format for ever-more unexpected forms. The phrases accompanying the pictures are rendered in the artist’s adopted and imperfect English, often resulting in some a hilarious and mysterious poetry of meaning. The overall effect is a wacky mixture of cartoon humor, lofty emotions, menace, and smoldering sexuality./ Rosie’s art anticipates today’s stretching of the boundaries in the canon of tattoo themes ... [He] was the real thing: immensely prolific, completely sincere, and driven by a passion for drawing that ultimately sought to satisfy only himself." - Don Ed Hardy

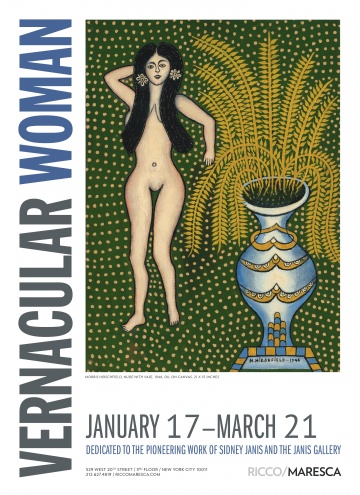

Various artists

VERNACULAR WOMAN

January 17, 2020 - March 21, 2020

Presenting depictions of women by self-taught, outsider, and anonymous artists in various media.

Frederick Sommer

Frederick Sommer: Visual Affinities

October 24, 2019 - November 27, 2019

Joe Massey

Shut Up: Joe Massey's Messages from Prison

September 12, 2019 - October 19, 2019

Thomas Lyon Mills

Thomas Lyon Mills: Liminal Space

July 11, 2019 - September 7, 2019

Renaldo Kuhler

Rocaterrania

May 9, 2019 - July 3, 2019

Playing Games: Chance, Skill, and Abstraction

March 28, 2019 - May 4, 2019

Back to all Member Galleries

Back to all Member Galleries