Krakow Witkin Gallery

10 Newbury Street

Boston, MA 02116

617 262 4490

Boston, MA 02116

617 262 4490

Krakow Witkin Gallery features contemporary art of all media by emerging and established regional, national and international artists. The overall focus is on Minimal, reductivist and conceptually-driven works.

Artists Represented:

Robert Barry

Mel Bochner

Robert Cottingham

Tara Donovan

Peter Downsbrough

Mike Glier

Jenny Holzer

Bronlyn Jones

Alex Katz

Ellsworth Kelly

Estate of Sol LeWitt

Allan McCollum

Julian Opie

Liliana Porter

Stephen Prina

Kay Rosen

Ed Ruscha

Estate of Fred Sandback

Richard Serra

Kate Shepherd

Kiki Smith

Shellburne Thurber

Ursula von Rydingsvard

Works Available By:

Josef Albers

Richard Artschwager

John Baldessari

Bernd + Hilla Becher

Daniel Buren

Dan Flavin

Philip Guston

Jenny Holzer

Donald Judd

William Kentridge

Robert Mangold

Brice Marden

Michael Mazur

Abelardo Morell

Robert Moskowitz

Bruce Nauman

Claes Oldenburg

Julian Opie

Sylvia Plimack Mangold

Robert Ryman

Richard Serra

Kiki Smith

Sarah Sze

Lawrence Weiner

“On Kawara"

“Echoing” Featuring works by Philip Guston, Sol LeWitt, Julian Opie and Liliana Porter.

“Julian Opie”

"Kiki Smith: Frequency"

“Relatives” Featuring works by Mike Bidlo, Liliana Porter, Jonathan Seliger and Haim Steinbach

"Fred Sandback Editioned Sculptures and Related Works on Paper"

"Gacing Grain" Featuring works by Sylvia Plimack Mangold Frank Poor Analia Saban.

"Richard Serra: 1985-1996"

Robert Bauer

Robert Bauer: Landscapes

March 1, 2025 - April 12, 2025

“Bauer's hand is intensely subdued, both distant and personal, inviting the willing viewer to be still.”

–Elaine Sexton

In 2014, Robert Bauer and Bronlyn Jones had a two-person exhibition with the gallery. Eleven years later, Krakow Witkin Gallery now presents a solo exhibition of Bauer's small landscapes in tempera and gouache, painted over the past five years.

“These are like conjured memories ... If they were only about depiction they'd be insufficient. It's their retraction from facts that makes them about the persistence of vision,” writes William Jaeger about Bauer’s work that was included in a 2017 exhibition at Skidmore College’s Schick Art Gallery.

Bauer paints with a keen attention to subtle detail through an exploration where he employs pencil notes, photographs, studies of other works sometimes of the same subject, and also more abstract memories of the time and place. Consistent with this layering is the artist's process of addition and subtraction. Bauer adds brushstrokes in a slow and steady process but just as carefully, he often sands and/or washes the painted surface so as to embed, subdue, and/or remove paint. The layering of sources and processes results in a balance of chance, choice, and control.

Poet and critic John Yau writes, “The reticence of Bauer's paintings mixed with his sensitivity to tonality and light suggests that he slows time down in order to register its passing.”

Robert Bauer was born in Iowa in 1942 and studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia. He moved to Boston in 1985 and currently lives in midcoast Maine. Bauer’s work has been included in exhibitions at the National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC, the Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art in Ridgefield, CT, the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York and Pratt Institute’s Manhattan Gallery. He is the recipient of three Massachusetts Cultural Council grants, two Pollock-Krasner Foundation grants in Painting, and he was a finalist in the 2006 Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery’s Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition. Bauer’s work is represented in public and private collections throughout the United States, including the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Harvard Art Museums.

“The atmosphere of hushed reverie”

–Elaine Sexton

Agnes Martin

Agnes Martin: 1973

March 1, 2025 - April 12, 2025

"My ego is not satisfied to idle along with inspiration or put up a great fuss called “suffering.” It has to be subdued. The only way is isolation. In isolation there is no comparison no stimulation. Ego finally is quiet enough so that one can pay attention to other parts of the mind. Then drawing is possible."

–Agnes Martin

Agnes Martin created her only major print project, “On a Clear Day,” towards the end of a seven-year period (1967-1974) during which she made no paintings. Martin had moved to an isolated mesa in New Mexico to live in solitude. She had spent the previous decade in New York City, a time during which she had critical and commercial success but disliked the distractions of the city, desiring a quieter, clearer place to live where she could make her “egoless” art, imbued with beauty, openness, and joy. Invited to make a print project in 1971 by Robert Feldman of Parasol Press, it took her two years to bring it to fruition. The results were the 30 silkscreens of crisp lines and grids that make up “On a Clear Day.” Upon completion of the project, the Museum of Modern Art in New York held an exhibition of the project and was the first museum to acquire the entire suite.

In a 1973 review of the MoMA exhibition, Thomas Hess wrote, “[Agnes] Martin has become the object of a cult and, as if to back off from her admirers, has done a series of silkscreen prints, currently shown at the Museum of Modern Art. In these, she has stripped her image of all hand-quivers and fluttering variations to emphasize the mechanics of its linear structure. The basic schema is a square grid. The number of vertical and horizontal lines is different, so each square is filled with either thin or wide rectangles. Thus one work has nineteen horizontal lines and nine vertical ones, yielding squat, wide, tile-like rectangles. Another has nine horizontal lines and 23 vertical ones, with narrow, upright tiles. Other combinations include: 8-10, 8-2, 12-9, 19-12, 9-23, 6-23. Counting the lines in a Martin composition suggests the chiming quality of her work... In Martin’s paintings on canvas, these developments were accomplished with a refinement of touch which led many of her admirers to applaud her manual dexterity and sensitivity. Now she chooses to direct us to the bare bones of her art and expose the imaginative leaps that underlie her craft.”

In her private writings, Martin affirms the balance of calculation and intuition in her compositions, stating, “My formats are square, but the grids never are absolutely square; they are rectangles … When I cover the square surface with rectangles, it lightens the weight of the square, destroys its power.”

35 years later, in 2008, Kevin Salatino, then Curator of Prints at Los Angeles County Museum of Art and now Chair & Curator of Prints & Drawings at the Art Institute of Chicago wrote, "Grander in conception than any of Martin’s paintings, “On a Clear Day” condenses through multiplication thirty ways of constructing a grid, of expressing happiness, beauty, freedom, and the impossibility of, though yearning for, perfection. Its individual parts, recalling the number of days in a month, imply the passage of time. Its title declares the long-sought-for clarity the artist had struggled to find in the barren New Mexican desert. One of the great works of graphic art of the late twentieth century, “On a Clear Day” announces with luminous clarity and conviction Martin’s return to aesthetic wholeness.”

“I was thinking about innocence, and then I saw it in my mind—that grid … So I painted it, and sure enough, it was innocent.”

–Agnes Martin

Victoria Burge

January 11, 2025 - February 15, 2025

In her first exhibition with Krakow Witkin Gallery, Victoria Burge explores and extends the historical relationship between the Modernist grid and handwritten notation. Using found imagery in 19th and early 20th century diagrams and charts sourced from research libraries, Burge makes works that both transform and honor pre-existing visual codes and their makers.

For works on paper such as Sterope or her Untitled slate objects, Burge begins with a coded textile pattern and lets the diagram serve as foundational inspiration, rather than as rule. She reimagines the weaving notations using typewriter keys or hand-drawn markings, transforming the patterns in such a way that would nullify them in their former context, rendering them indecipherable to a weaver (a line extended just a hair too far, a mismatched pair of symbols, or a point left idling in space). Within the mark making, imperfections such as an off-center circle or a not-quite-straight line hint at the human labor inherent in even the most formal of constructions.

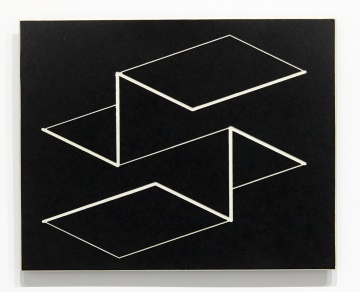

Sol LeWitt

Sol LeWitt: Early Drawings (1968-1975), Related Structures, and Prints

September 7, 2024 - October 5, 2024

Today, Sol LeWitt is equally known for his two- and three-dimensional works, but in the late 1940s, through about 1960, the artist focused on painting as well as drawing, and printmaking. By the mid-1960s, his paintings had transitioned through deeply impastoed paint, to paint on dimensional supports, to a focus on fully three-dimensional form. With this new-found focus, LeWitt began engaging skilled craftspeople to assist in the construction of his pieces (he called the works, “structures”). In order to communicate what he wanted, he drew fabrication diagrams using simple perspectival lines. Horizontal, vertical, and diagonal (in two directions) lines served LeWitt’s purpose of communication. Shortly after he started using this sort of diagram, he also began exploring drawing with these same four directions of lines (first on paper, then on walls) but now as the imagery with no external referents. With some time, he came to call this simplified imagery, “Lines in Four Directions.” The current exhibition focuses on early works made between 1968 and 1979 that speak to his exploration of “Lines in Four Directions” and that imagery’s relationship to concurrently-made three-dimensional works.

Throughout the exhibition, works are arranged so as to provide both context and counterpoint for each piece. Several examples are below:

A three-dimensional 1979 metal open cube structure has a grid of 3×3 cubes within it, so that it makes not just the 27 individual cubes but one larger overall cube, as well. Depending upon how one views the piece, one sees a dynamic arrangement of lines in four directions in space. Paired with this work, a 1971 etching consists of a dense field made entirely from lines in four directions. While the etching exists in two dimensions and the cube in three, the aesthetic and the exploration are deeply entwined.

A surprising work to be included in a solo exhibition of Sol LeWitt’s is an 1887 collotype by Eadweard Muybridge. Muybridge’s series of photographs, breaking down the stages of human motion from multiple equally-important vantage points, informs the grids of LeWitt’s works, which utilize Muybridge’s scientific method for LeWitt’s formally-reduced investigations. LeWitt gave this particular example of Muybridge’s work to a friend and colleague in a frame of his own making. Flanking this piece are two iconic works of LeWitt’s. A 1974 single open cube (defined by the 12 edges of a cube, rendered in metal that has been painted white) stands to the left of the Muybridge. To the right is a 1969 drawing, “Four Varieties of Line Direction.” Both works speak to LeWitt’s reductivist inclination. For the cube, while it initially appears simple, there are infinite ways to experience the defining border lines as well as what the cube “frames” through it. For the 1969 drawing, as described above, what once had been used merely as tools to describe something else, have become the focus of the exploration and now stand as an elegant drawing of quadrants of four different “sets” of parallel lines where the balance between the hand-drawn and the ordered, along with the contrast between the different directions of the lines, co-exist and provide quiet tension.

These juxtapositions are arranged in honor of LeWitt’s own methodology of presentation. “Straight Lines in Four Directions & All Their Possible Combinations,” a suite of etchings from 1973, exemplifies this gesture. Over fifteen sheets of paper, the artist presents lines in four directions and (and per the title of the work) all their combinations. The sixteenth sheet (the “colophon”) provides a diagram of the 15 in their proper arrangement and in the space of the 16th, places the text describing the project, so that when one hangs the work as illustrated on the 16th sheet, there is a set of nesting “images” where each smaller version is, in a way, equal to the larger one (the overall project is the same as the image of the 15 arranged on the 16th sheet, the text on the 16th sheet is equal to the entire project, etc.).

With all of these comparisons, differences, and relationships, it becomes clear that a key to an understanding of LeWitt’s work is his sense of equality. Three-dimensional and two-dimensional, open and closed, dense and sparse, big and small, imagery and text, idea and object, etc. were treated by LeWitt as equally significant. This exhibition presents the audience an opportunity to celebrate the eye and mind with which LeWitt approached life.

Fred Wilson

Fred Wilson: Master Plan(s)

September 7, 2024 - October 5, 2024

“I want people to see these works as I see them and I try to, without hitting people over the head, allow them to think … and either make sense of it or not.” (Fred Wilson)

Fred Wilson (b. 1954, Bronx, New York) has long investigated the meanings of symbols and objects as part of his multidisciplinary, research-based practice. Through alteration, juxtaposition, decontextualization, and selection, among other actions, the artist provides opportunities for new interpretations and associations that reframe social and historical narratives. Working across sculpture, painting, photography, collage, printmaking, and installation, Wilson imbues reclaimed images and objects with personal and historical importance. Legacies of colonialism and erasures of Blackness in Western European art are often the subject in his exchanges with these objects of different geographic and temporal origins.

For the current exhibition at Krakow Witkin Gallery, an early sculpture is juxtaposed with a rare, complete suite of photogravures to show both the depth and breadth of the artist's visual and intellectual explorations.

For "Art World" (1994), Wilson has taken a found globe and selectively removed Latin America, Eastern Europe, Africa, and most of Asia. Wilson has stated, "At this point I had sort of shifted it because it was really about that time and that the art world was only the United States and Europe, and all these other places were just not there." The art, though, is not just highlighting the absence, but what happens to the globe with that absence. The physical changes to the found object reveal to the viewer a thin structure supporting an incomplete, warped shape that one can see through but can no longer rotate smoothly. These are changes to the object that are both physical alterations and also serve as lenses with which to see the metaphorical ramifications of a limited "art world."

"THE MASTER PLAN or In Between the Big Bang and Modern Art is the Restroom" (2004-2009) consists of 22 photogravures where Wilson has employed specific gallery floorplans from visitor orientation maps of eighteen European and North American museums of anthropology, art, cultural or natural history. Omitted from these maps are all but a few words and icons of collection care terminology or visitor services signage. Displayed as an immersive installation of evocative but anonymous abstract forms, a viewer can explore one's own "master narrative" by comparing one plan or symbol usage to the next. The subtitle, "In Between the Big Bang and Modern Art is the Restroom" evokes an evolutionary perspective, the legacy of colonialism and imperialism, still embodied today in the organization of materials cared for by Western museums, supported in most cases by a hierarchically distributed space division. Hopefully, while the removal of information leaves room for assumptions, indicators highlighted by the artist enable a clearer path of thinking.

Wilson recalls that, at the beginning of his career, "working simultaneously in the educational department of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the American Museum of Natural History, and the American Craft Museum made me wonder about how the environment in which cultural production is placed affects the way the viewer feels about the artwork and the artist who made these things."

The artist’s early work was directed at marginalized histories, exploring how models of categorization, collecting, and display exemplify fraught ideologies and power relations inscribed into the fabric of institutions. His groundbreaking and historically significant exhibition "Mining the Museum" (1992) at the Maryland Historical Society, radically altered the landscape of museum exhibition narratives. As interventions, or “mining,” of the museum’s archive, Wilson re-presented its materials to make visible hidden structures built into the museum system, and American Society as a whole.

Commenting on his unorthodox artistic practice and how it has changed over time, Wilson has said that, although he studied art, he no longer has a strong desire to make things with his hands: “I get everything that satisfies my soul from bringing together objects that are in the world, manipulating them, working with spatial arrangements, and having things presented in the way I want to see them.”

His installations lead viewers to recognize that changes in context create changes in meaning. While appropriating curatorial methods and strategies, Wilson maintains his subjective view of the museum environment and the works he presents. He questions (and forces the viewer to question) how curators shape interpretations of historical truth, artistic value, and the language of display—and what kinds of biases our cultural institutions express.

One Wall, One Work: Sherrie Levine, Walker Evans, the Library of Congress, and others: The Burroughs Family (a collection)

September 7, 2024 - October 5, 2024

The current exhibition, “Sherrie Levine, Walker Evans, the Library of Congress, and others: The Burroughs Family (a collection)” took 88 years to come together. Below is a recounting of how and why it was assembled:

In June of 1936, Walker Evans traveled to Alabama with writer James Agee on an assignment for Fortune magazine to produce a new installment in a series of articles on the Depression and its effect on what the magazine considered “average” Americans and specifically for this assignment, sharecroppers. To do this, Evans took a leave from the Resettlement Administration (which was soon succeeded by the Farm Services Administration) where he was working, with the agreement that the negatives would become property of the US Government. While Fortune declined to print their article, Agee and Evans continued the project, ultimately publishing the book, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, in which Evans’s photographs prefaced Agee’s text.

In Alabama, over eight weeks, Agee and Evans had become familiar with three families of farmers in Hale County: the Fields, the Tingles, and the Burroughs. The writer and the photographer embedded themselves in the lives of these families, sharing their day-to-day experiences. Evans made photographs of the families, their homes, and their ways of life. In Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, Agee notes that the Burroughs’ home, despite appearances, was only eight years old when the pictures were made. In addition to farmland and housing, Floyd Burroughs also leased farm equipment and, as payment, surrendered half his harvest to his landlord. He regularly ended the year in debt. Evans’ photographs neither romanticized nor criticized their subjects, they presented them.

In 1981, 45 years after Evans photographed these families, Sherrie Levine re-photographed reproductions of Evans’ work straight out of a book for a project she titled “After Walker Evans.” Evans was one of several male “artist hero” of classical Modernism that Levine had chosen to reproduce work by as a way of questioning traditional notions of the male artist as authority and/or genius. Levine’s use of the prefix “After” in her title acknowledged the chronological precedent of Evans while also referring to the widely accepted practice in the history of art of making copies “after” established masterpieces. By claiming these existing photographs as her own, as well as titling them as she did, Levine asked questions about authenticity, ownership, and originality, as well as how these aspects have traditionally been the basis for valuing works of art. Levine has stated, “The pictures I make are really ghosts of ghosts: their relationship to the original images is tertiary, i.e., three or four times removed."

The use of the word, “ghost” by Levine makes sense for her own work and it also resonates for Evans’ approach and the “lives” of the negatives from the Let Us Now Praise Famous Men series as, over the course of Evans’ life, the negatives had been used to make prints by Evans and by his associates, as well as by the Library of Congress itself (the Federal organization that manages the FSA holdings and owns the negatives). The definitions of the words “authentic,” “original,” and “vintage” are murky when it comes to these works.

Similarly, over the years, Levine had re-printed some of the images from “After Walker Evans” in various sizes (from approximately 3 x 5 inches to 9 x 13 inches). At larger sizes, one sees the quality of the reproduction being captured as much as the image of the Burroughs family, themselves. The 1981 prints were praised as a feminist hijacking of patriarchal authority and a critique of the commodification of art. Little comment has been made, specifically, about the various prints Levine has made since 1981.

With this sort of grey-zone being seemingly significant for Levine’s practice and also for the lives of Evans’ works, a presentation fully engaging the “ghosts” seems an appropriate way to present both artists’ works together. Central in the presentation is Evans’ own print, “Burroughs Family, Hale County, Alabama,” (the image of the entire family, standing against an exterior wall of the family home). Above that is Levine’s “After Walker Evans: 1,” (the image of most of Floyd Burroughs and his neighbor’s children standing against/near a porch post). Surrounding these two “original” photographs are other photos, all different images of the Burroughs, all from Evans’ negatives. The exhibition, as a whole, has vintage prints by Evans and by associates, and vintage prints by the anonymous printers at the Library of Congress. Also on exhibition are a number of 2024 digital prints that come directly from scans of the original negatives and were recently printed by the Library of Congress.

Furthermore, also included in the exhibition is the original 1941 book, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. It first came to publication with 30 images by Evans in 1941 and was met with little acclaim. It was reissued in 1960 (now with 61 images) and has since become a “classic” of American literature. Since that time, the book has been reprinted numerous times (with selective editing and re-sizing of the various images). Nine versions of the book are on display and available for perusing.

As a whole, the exhibition hopes to honor both Levine and Evans, as well as the numerous other people who have played significant rolls in these projects (Agee, the Burroughs, Library of Congress, and many others), and also attempts to bring forth the problematics of both artists’ practices so that they can be appreciated.

(The group of books and photographs are being kept together and sold as one collection.)

Michael Mazur

Michael Mazur: Paintings 1970-2008

June 15, 2024 - July 19, 2024

Join us for the public opening reception on Saturday, June 15th, 2024 from 3pm - 5pm

Julian Opie

April 20, 2024 - June 1, 2024

Join us for an opening reception with the artist on April 20, 2024, 3pm - 5pm

Whom

September 9, 2023 - October 14, 2023

Featuring works by

Christian Boltanski, Robert Fillou, Lyle Ashton Harris, Cary Leibowitz, Sherrie Levine, Liliana Porter, David Robbins, Thomas Ruff, August Sander, Cindy Sherman, Laurie Simmons, Lorna Simpson, James Van Der Zee, and David Wojnarowicz.

Donald Judd, Gertrud Goldschmidt (Gego), Sol LeWitt, Brice Marden, Agnes Martin, Ad Reinhardt

Lines and Planes and Space

March 11, 2023 - April 22, 2023

Featuring works by Gertrud Goldschmidt (Gego), Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, Brice Marden, Agnes Martin, and Ad Reinhardt

With a majority of the art made between 1963 and 1973, the current show presents six artists’ strong yet quiet works. The relationships between line, plane, and space play critical rolls in each artist’s exploration and hopefully, by presenting the pieces together, a viewer can both appreciate each individual piece and also explore the potential conversations between works.

Cindy Sherman

Cindy Sherman: 1975-1980

March 11, 2023 - April 22, 2023

Cindy Sherman rose to prominence with her now iconic series of works, the “Untitled Film Stills” (1977–80), a series of photographs in which the artist captured herself enacting seemingly familiar pop culture clichés. The various works in the current exhibition were made either before or during the period of the “Untitled Film Stills.” At this critical early stage in her work, Sherman was already critiquing the construction of identity, whether in art, fame, and/or photography. As has been true throughout her career, Sherman drew attention to the artificiality and ambiguity of stereotypes and thus presents a much more complicated reality.

Abelardo Morell

Abelardo Morell: In the Footsteps of van Gogh

January 14, 2023 - March 25, 2023

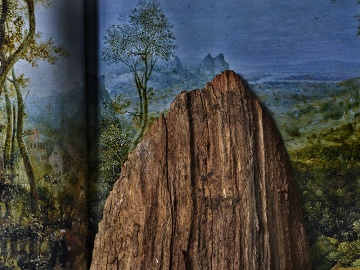

In June 2022, I went to Arles, Saint- Remy and other places in the south of France to make pictures where van Gogh painted. In locating myself within his landscape, I hoped that my pictures would contain – and be touched by – some of the spirit and light in his paintings. Clearly, I did not produce any new “van Goghs,” which is a good thing because I didn’t want to make copies!

Happily, what I came up with was my own take on the light and land in Provence and yet, I think, my landscapes, as different as they may be from the painter’s, still evoke something of his vision. I also believe that some of the images I made suggest the look and atmospheres captured by other 19th century French landscape painters who influenced van Gogh.

The patina and strangeness of the surface that appear in several of my images are products of a photographic tool I call “tent /camera.” I designed this device to allow me, in a periscope-like fashion, to project views of a nearby landscape directly onto the very ground where the tent sits. My camera, on top of the tent, captures a ‘visual sandwich’ comprised of the scenery and the details of the ground all at once, in one picture. And it is in this real/surreal melding of optics, photography and art history where my pictures dwell, creating, I hope a middle world – where both the expansive and the particular can reside at the same time. – Abelardo Morell

Sol LeWitt, Kiki Smith, Martin Puryear, Robert Cottingham and others

Lines in Four Directions Over 450 Years

January 14, 2023 - April 22, 2023

“Lines in Four Directions over 450 Years” explores the conceptual, formal, and social aspects of one particular technique from a contemporary perspective. As such, the collection of 28 works by 26 artists hang together on one wall as the latest iteration of Krakow Witkin Gallery’s “One Wall, One Work.” The unifying characteristic in the group is “hatching,” a technique used in Western drawing and printmaking mostly from the 1300’s and on. Hatching uses closely spaced parallel lines and, traditionally, it provides an image with depth, shade, and/or tone. “Crosshatching” uses another set of parallel lines which overlap or cross the hatching to provide further variations in shading. In the late 1960’s, Sol LeWitt used the technique of crosshatching and isolated it from its illustrative purpose. This provided him a visual vocabulary with endless and powerful iterative potential. With LeWitt’s work as inspiration, Krakow Witkin Gallery’s presentation explores differences between artists, techniques, and time periods, all while highlighting issues of equality, innovation, power, and space.

The particular, visual impetus for the exhibition began with two of LeWitt’s works, as well as two other artists’ works. A brief description of each of these works is below:

• Sol LeWitt

Two line etchings from 1971 by LeWitt are examples of the artist’s use of regular and hand-drawn “lines in four directions” (vertical, horizontal, diagonal/left, and diagonal/right lines). The combination of lines used in these works was an “imagery” that LeWitt became engaged with by 1965 as he was then using the four types of lines to make construction diagrams for and drawings of his three-dimensional structures. By 1968, he was exploring the lines purely in two dimensions (no longer using them only for representing something in three dimensions). He made drawings of layered and juxtaposed lines in various combinations (first publicly seen in the now seminal “Xerox Book” and soon thereafter in his first wall drawing). By 1971, this imagery was iconic for LeWitt. One of the two etchings on view shows a progression of layers of the lines, from one to four. The second consists ‘only’ of a field of all four directions of lines overlayed. Importantly, LeWitt found both approaches equally important. Through the combination of imagery where all line directions are important and the seriality where all variations are equal, LeWitt presented visually compelling works that are statements about egalitarianism (not a surprising theme from an artist who consistently supported and championed artists of many different backgrounds).

• Diana Scultori

Scultori was among the first women, ca. 1575, to get a Papal Privilege to sell her prints in Rome (a “Papal Privilege” was a legal situation that helped her sell her work without fear of what would later be called copyright infringement). This narrative is, in and of itself, compelling as it paints a picture of a smart, strong, independent, and talented woman in 1500’s Rome. To add to the background of the work currently on view, it is not definitively known whether the subject matter is “Esther seated at a table to the left speaking with Ahasuerus and Haman” or “Aspasia, Socrates, and another philosopher.” Having multiple readings of the imagery in the print is significant. The alignment of Esther (a queen who calls a sly villain to task) with Aspasia (a philosopher and teacher) provides the protagonists with mutual support in unsupportive social structures of both the narratives’ time periods and Scultori’s. Perhaps Scultori left the narrative open-ended so that multiple meanings could be mutually beneficial? This approach is, in a way, similar, if one can think abstractly, to the layers of LeWitt’s lines. Along with this conceptual alignment, there is a visual one, too. Scultori primarily used straight parallel lines in various overlapping ways to create her imagery. In many of the planar areas of the image, one can see etching rather similar to that of LeWitt’s.

• Jacques Villon

Villon, in the 21st century, is primarily known as the brother of Marcel Duchamp. At the famed 1913 Armory Show, all of Villon’s work sold and for a time thereafter, the brothers were almost equally famous. With that said, Villon, in addition to being a painter and designing the famed stained glass for the cathedral in Metz, was also an accomplished printmaker who brought the language of Cubism to a print-collecting audience. He called his linear imagery, “constructive decomposition.” This ‘decomposition’ used just straight lines in various combinations so as to create both legible imagery as well as a firm balance among the foreground, background, and all areas in between. Much like LeWitt (or perhaps it should be said in reverse…), Villon created compositions with no hierarchy of gestures.

In addition to these artists’ works, the topic of heraldry (the system by which coats of arms are devised, described, and regulated) plays a key roll in the formation of the exhibited collection. In the history of heraldry, lines in four directions (along with other combinations, patterns, etc.) were used in monochromatic representations to indicate what a “full-color” emblazon would be (accessible, multi-color printing would come hundreds of years later). Various charts from the 1700’s (and forward) are exhibited as elegant, ordered examples of combination and variation.

The collection began by putting the above works together and then spending the next few years slowly assembling a family of works that could live together and expand on the works’ conversations, both visually and conceptually. The full list of artists included are George Aikman, Cherubino Alberti, Cornelis Bloemaert, Louis Jacques Cathelin, William Charles, Daniel Nicolaus Chodowiecki, Robert Cottingham, Henri Fantin-Latour, Gego, Pieter Holdsteijn the Younger, William Hogarth, Käthe Kollwitz, Sol LeWitt, Mortimer Menpes, Thomas Milton, Crispin De Passe the Younger, Martin Puryear, Guido Reni, Adamo Scultori, Diana Scultori, Kiki Smith, Henry Ossawa Tanner, David Teniers the Younger, and Jacques Villon, along with two that are unidentified at the present time.

Daniel Buren, Vik Muniz

Daniel Buren & Vik Muniz: Continuity

October 22, 2022 - December 17, 2022

While visually quite distinct, the works of both Daniel Buren (b. 1938, Boulogne-Billancourt [Paris], France) and Vik Muniz (b. 1961, São Paulo, Brazil) engage the subject of continuity.

—

“A certain type of work is able to journey from one place to another, provided that it follows certain precise rules or instructions. This is the case with works that can be “re-performed” the same way a work of music can be performed over and over again. Each “re-performance” generates new readings and interpretations, originating from each new site in which the work is installed.”

Daniel Buren

Daniel Buren found a pattern in 1965 (an 8.7 cm-wide stripe that was on a bolt of awning fabric) and has continued to work with it for almost sixty years. The specificity of the stripes is not meant to be read as content but as a visual tool. Over the years, Buren has created interventions using these stripes in, on, and out of various materials. These interventions only work when they are “in situ” as the materials have to interact with the space in which they are placed and that interaction results in the work. The gestures Buren makes address questions of the way space can be used, appropriated, and revealed in its social and physical nature. For the current exhibition, three works (from 1979, 1993 and 1998) each consists of 25 elements dispersed in a prescribed manner across a full wall. Each piece balances between assumptions, awareness, extrapolation and interpolation, all the while complicating the relationship between art and the structures that frame it.

—

In the evening of September 2nd, 2018, a fire consumed the entirety of the National Museum in Rio de Janeiro, burning nearly all of its historic and scientific collections amassed over the course of two hundred years. The blaze destroyed the Egyptian, pre-Colombian, and indigenous Brazilian collections, an entomology department with over five million specimens, South American dinosaur fossils, and Luzia, the earliest humanoid skull found in the American continent. The museum was Vik Muniz’s favorite cultural institution in the city, a place he often visited with his children.

“I cried upon learning of the fire as if I had lost something personal, some kind of string that held the insanity of my present together. Brazil is a young country with a strategic neglect for its history and a ravenous appetite for the instantaneous. No other place in Brazil combined so much history and wonder. We already live with an increasing deficit of reality and seeing history go up in flames made me feel groundless, trapped in an infinite present. We can only be creative in a world of facts and tangible realities. A post-truth, nihilistic cultural environment inspires the opposite of creativity, which is baseless pragmatism. When the mind wanders entirely ignorant of time, illusion becomes a means of confinement.”

Vik Muniz

Muniz contacted the museum to see how he could help and learned of the extraordinary work of meta-archeology that the scientists were doing in recovering what little was left from the devastating incident. He also learned of the limited resources they had to do their jobs. The archeologists agreed to provide Muniz with whatever material passed through the sifters and shared the precise location where the ashes had been collected. Working from extant images, Muniz re-created the objects with material from their own ashes and photographed them. Alongside these photos will be a series of objects created in collaboration with the Federal University of Rio and Pontificia Universidade Católica. These 3D printed objects are derived from existing tomography files of the museum’s now-destroyed items, built using the ashes collected from the sites of their specific displays. The results, a body of work Muniz calls, “Museum of Ashes,” are a meditation on materiality within the context of the predominantly virtual relationship we maintain with the past. By fusing the form and the material of historical evidence, Muniz not only attempts to rescue the memory of such objects but also reminds us that life, as well as art, is the product of an interplay between mind and material.

Maggi Brown

Maggi Brown: 1988-2021

September 10, 2022 - October 15, 2022

“Alive as a hive of bees yet sometimes serene, Brown’s paintings are like communities of marks. Like people, the marks work for and against one another. They accumulate baggage. They accrue into something larger than themselves.” (Cate McQuaid)

Maggi Brown and Krakow Witkin Gallery celebrate 35 years of working together with a survey of paintings from 1988 to 2021. The exhibition presents Brown’s loosely rendered geometric patterns, fields of curvelinear strokes, abstracted “writing” and other repeated marks. While these painted and carved gestures are quite significant, Brown has always felt confident covering over or even painstakingly scraping away layers of masterfully applied pigment. She selectively adds, obfuscates and/or removes both small and large areas. The various sections become equal, with the ‘history’ brought to the same level as the newest (top) layers. As important as this scraping is how Brown engages a sense of illumination. What can seem like glare (from ambient light) or a shadow (cast from within a room onto the painting) is often a subtle but confident change to the paint’s tints and/or tones, thus creating gritty devotions to ethereality. For Brown, the time to make the painting, the time ‘depicted’ within it and the time it takes a viewer to comprehend the physical and imagistic aspects of the work are all equally important. This exhibition presents the opportunity for the viewer to see this not only within individual works but on a macro (35+ years) scale.

“In a broad sense, I am interested in the connection between things which are opposed, what they have in common, and what kind of visual statement they make when combined. For me, all art that is meaningful deals in multifarious ways with the reconciliation of opposites.” (Maggi Brown)

Mel Bochner

April 23, 2022 - June 1, 2022

Krakow Witkin Gallery announces an exhibition of large-scale silkscreens that Mel Bochner has made over the past five years. For these new works, Bochner has photographed the Plexiglas blocks with which he has made his monoprints and then printed those photos as multi-color screenprints. The imagery shows not only the texts, but the scrapes, chips and imperfections in the well-worn blocks. Printing this imagery with high contrast color juxtapositions, Bochner explores the relationship between the visual and the textual (when and how one moves between viewing, reading and deciphering a work of art). With no one fixed voice, he has made pieces that are confounding, confusing, dynamic, and humorous simultaneously.

As a bit of history, in 2001, Bochner began a series of works engaging everyday speech by using synonyms derived from the latest edition of Roget’s Thesaurus. Bochner was inspired by the Thesaurus’ then-new permissiveness to broaden his linguistic references juxtaposing proper with vernacular, formal against vulgar, high against low. Twenty-one years later, and still drawn from Roget’s Thesaurus, as well as dictionaries of slang, the language in the recent works can vary from the casual to crude and can simultaneously be read as defeatist and elated, all while engaging social issues of the day.

Roberta Smith wrote in a New York Times review, “The new Bochners unleash something malicious, sharp and funny that has always lurked beneath the surface, conveying the rage of life while maintaining the artist’s characteristic surface of elegance, intellect and formalism. In a sense they are Expressionistic works, filled with pain, and grinning and bearing it.”

Simultaneous with the exhibition, the Art Institute of Chicago has just opened a major retrospective of Bochner’s drawings. It is on view through August.

Mel Bochner [born 1940] is recognized as one of the leading figures in the development of Conceptual art in New York in the 1960s and 1970s. Emerging at a time when painting was increasingly discussed as outmoded, Bochner became part of a new generation of artists which also included Eva Hesse, Donald Judd, and Robert Smithson – artists who, like Bochner, were looking at ways of breaking with Abstract Expressionism and traditional compositional devices. His pioneering introduction of the use of language in the visual, led Harvard University art historian Benjamin Buchloh to describe his 1966 Working Drawings as ‘probably the first truly conceptual exhibition.’ Over the course of a career that has spanned nearly six decades, Mel Bochner has been at the forefront of Conceptual Art, producing thought-provoking work in nearly every medium: drawing, painting, prints, photography, sculpture, books, and installations.

León Ferrari

León Ferrari: Heliografía

March 3, 2022 - April 9, 2022

León Ferrari was born in Buenos Aires in 1920. His father, Augusto, was an Italian artist who painted religious frescoes and helped build and restore churches. Augusto advised his son not to choose an artistic career because of the poor financial prospects, so León studied engineering at the University of Buenos Aires. He made numerous trips to Italy, where he worked as an engineer and began making abstract art. In 1960, he had a show of his abstract art in Buenos Aires. By 1965, he became known for his art that often included provocative social and political critiques of war, social inequality, discrimination (sexual, religious, and ideological), and abuse of power. He castigated the Argentine government for human rights abuses well before the military took full control in 1976. Fearing reprisal, he went into exile in Brazil from 1976 to 1991. His son, Ariel, was abducted by the military shortly thereafter (and is presumed dead) as part of the Guerra Sucia (Dirty War) in Argentina.

Within a few years of relocating to Brazil, partly inspired by the mass quantities of people he saw daily on the streets and partly inspired by political beliefs, Ferrari began the body of work now on view at Krakow Witkin Gallery. ‘Heliografía’ is a process most often associated with architectural blueprints. The main imagery in Ferrari’s heliografías was formed from Letraset (architectural symbols, precut as rub-on stickers). In the current presentation, the vast majority are of a human figure walking, as seen from a bird’s-eye view. Ferrari used huge quantities of this one figure to create imaginary scenarios/environments/plans that can be seen as absurd, pointed, wry, and/or existentially dark. In one work, a repeated ‘line’ of this figure walk in a permanently looped pattern. In another, two organized masses of the letraset figure stand facing in opposition. In a third work, grids of the figure are facing alternating directions so as to create an almost patchwork-like image, somewhere between a crowd and a blanket. While the heliografías point out the dangers of blindly following a particular pattern or movement, they also engage issues of order versus chaos, collective versus individual and oppositional versus intersectional.

It is important to recognize how Ferrari engaged the physical objects/pieces of paper of the heliografías. In the 1980’s he printed them and signed them. He would fold and mail them to friends and colleagues.The works existed somewhere between being blueprints, mail art and maps. The folding is a key element in that the images on the paper are embedded in the creases and undulations (from the folding of the paper) to create works that are images, objects and sculptures, all at once. Furthermore, when Ferrari first started making the pieces in the 1980’s, he would sometimes denote that they were part of an edition and other times he would not. In the 2000’s, he revisited the imagery and realized that in order for the process of their making to be resonant with the imagery, message and object, he needed to list them as editions of infinity (endless, like the movement in the imagery) and to not denote which # of the edition they are (denying individuality), thus all the works in the current exhibition are listed as “x/infinity,” balancing the importance of political content with formal and technical exploration.

A world-renowned artist, Ferrari’s work is included in major museum collections including the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), NY; the Casa de las Americas, Havana; Daros Latin America, Zurich; and the Centre Pompidou, Paris among many others. The artist received the prestigious Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement Award at the Venice Biennale in 2007. In 2009, New York’s Museum of Modern Art showed León Ferrari’s and Mira Schendel’s work in its dual retrospective exhibition, “Tangled Alphabets.” In 2021, the Museo Reina Sofía (Madrid), Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven) and Musée national d’Art moderne-Centre Pompidou (Paris) launched a survey exhibition that is currently traveling between museums.

Kay Rosen

Kay Rosen: Lists, 1989-2021

September 18, 2021 - October 23, 2021

Kay Rosen makes her work by finding, assembling, arranging, composing, simplifying and/or complicating letters and words. The current exhibition, “Kay Rosen: Lists, 1989-1991” consists of every work the artist has made with the ‘list’ form. With Rosen’s direction, a list can be an accumulation, juxtaposition, narrative and/or puzzle. As opposed to traditional grammar, the myriad options of how a list exists has given Rosen both structure and freedom with which to engage formal, social, and political topics. The pieces in the show are in and on a wide range of media (award ribbons, book covers, etching, graphite, handouts, letterpress, periodicals, silkscreen, video and wall painting, among others) and thus show the depth and breadth with which Rosen works. In conjunction with the exhibition, each work in the show now has an associated text (all are available on the website) to further add to the experience of viewing/reading

Kay Rosen has been the subject of numerous articles, reviews, and group and solo exhibitions, including in 1998 a two-venue mid-career survey entitled “Kay Rosen: Li[f]eli[k]e,” curated by Connie Butler and Terry R. Myers at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art and Otis College of Art Design. She has been the recipient of awards that include a Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship in 2017 and three National Endowment for the Arts Visual Arts Grants. Her work is included in many institutional and private collections. Rosen taught at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago for twenty-four years. She was born and raised in Corpus Christi, Texas and lives in New York City and Gary, Indiana.

Concurrent with Krakow Witkin Gallery’s “Kay Rosen: Lists, 1989-2021” is Rosen’s “New Work 2020-2021,” a solo exhibition in New York at Sikkema Jenkins & Co.. The show features acrylic gouache paintings on paper, enamel paintings on canvas, and two wall murals. Produced over the past 18 months, these works respond to the fear, isolation, and anxiety experienced by the artist during that time.

Fred Wilson

Fred Wilson: Flags

April 22, 2021 - June 3, 2021

My flag paintings are about the zenith of the twentieth-century history of African people. The majority of them were created during the 1950s and 60s — the years of liberation from colonialism. They embody a “modern’ aesthetic and idea. They contain the typical tropes of flags: the colors representing the green beauty and fecundity of the land, the blue of the majestic sky or water, and the red blood shed in the fight for freedom. But often they also contain black, symbolizing the people. In as much as some mimic the “tricolore” of the colonizing countries, the different colors set them apart, often in stark contrast to their European counterparts. The colors can represent tribal, cultural, religious, and political identities as well as national ones, sometimes simultaneously. Conversely, the missing colors also speak to the fluid and in flux nature of Africa and its national identities. My flag paintings are here to reveal, through a curious absence of color, the dynamic nature of African visual history and thought. They are perhaps intentionally perplexing, to make viewers question and perhaps rethink their assumptions. - Fred Wilson

Sarah Charlesworth, Giulio Paolini, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Shellburne Thurber

Remake

April 22, 2021 - June 3, 2021

Group exhibition featuring Sarah Charlesworth, Giulio Paolini, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, and Shellburne Thurber

Josef Albers

Josef Albers: Structural Constellations

April 15, 2021 - May 13, 2021

Krakow Witkin Gallery announces a focused presentation of Josef Albers’s “Structural Constellations”.

Albers began exploring machine-engraved laminated vinyl at approximately the same time he began the first “Homage to the Square” paintings. As Jeannette Redensek explains, “to study the perception of color, the painter restricted himself to just four compositional formats for the next twenty-six years; to study perception of space, he limited himself to linear constructions.”

To make the “Structural Constellations”, Albers cut lines into a laminated plastic called “Vinylite” (or “Resopal” in Germany). To do so, Albers engaged machine shops (which normally would be engraving signs for dentist and lawyer offices or even the instrument panels for submarines). The process consists of using a pantograph, where the movement of tracing Albers’s template with one arm of the device produces identical movements in the second arm (which has a router to cut the shape into the laminated plastic). A pantograph allows for multiple size variations from the same template. Furthermore, the laminated vinyl has a black top layer and a white under-layer. The router cuts through the black, exposing the white, so as to create both a sculpted recess and a white line. This simple process, combined with the illusion within the imagery, demonstrates one of Albers’s true gifts – the delicate balance between complexity and simplicity.

“Albers’s art is rational but also playful. The artist was inspired by the same scientific, poetic and consummately generous spirit that compelled Kandinsky to write Point and Line to Plane. But in his New Haven, Connecticut, studio in 1950, Albers had as much in common with Concept artists of the 1960’s and 1970’s as with Bauhaus painters of the 1920’s. He can in fact be seen as an intellectual and artistic bridge between the generations. For him the idea was ascendant, foremost, predetermined. An artist was but a humble craftsman enacting conclusions.” (Redensek)

In putting this project together, Krakow Witkin would like to extend many thanks to Jeannette Redensek of The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation for her expertise and generosity of time and spirit. Furthermore, Cristea Roberts Gallery, the representative of the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation for editioned works, are incredible colleagues with which to collaborate not just on this project, but in general. In their London gallery this coming December will be the exhibition, “Josef Albers: The Early Prints 1916-1950”. Also forthcoming is “Anni and Josef Albers: Art and Life” at Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris.

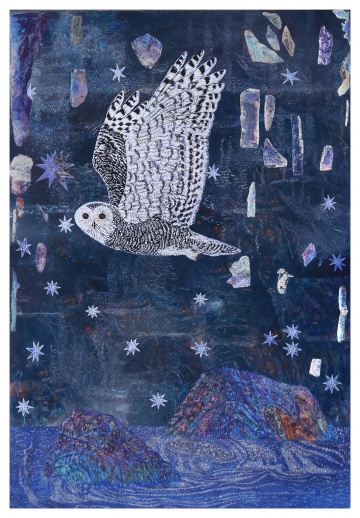

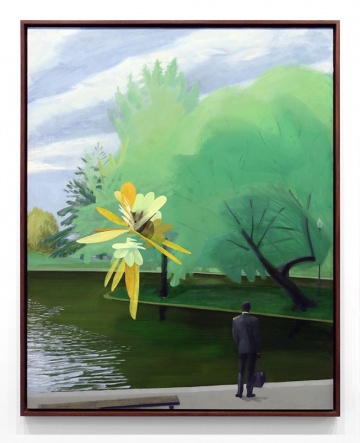

Mike Glier

Mike Glier: Bird Songs of the Boston Public Garden

March 20, 2021 - April 24, 2021

In 2019, Mike Glier and Krakow Witkin Gallery began planning for Glier’s next exhibition at the gallery. As so much of his work is about site and sight, Glier proposed to make an exhibition engaged with a location near the gallery. Choosing the Boston Public Garden (a Victorian public park dating to 1837 that is steps away from the gallery), Glier spent the week of May, 2019 photographing the Garden and drawing the sounds of the birds.

“My artwork is motivated by the rupture between humankind and the natural world and the environmental destruction that flows from this self-inflicted wound. The bird songs which persist in urban spaces like the Public Garden, however, are testaments to unity. Each “doo doo, dee dee” and “twit twit” that resonates off the pavement and brick of the city is a song of reconciliation that says nature and culture are not separate things, but are a single entity, the living world.” (Mike Glier)

In the Garden, before putting pencil to paper, he closed his eyes, took an inventory of his senses and registered the fullness of the place, from sound (traffic, human conversations, songs among the birds) to touch (the bench, the sun, the dew) to smell (daffodils and Dunkin’ Donuts).

“The language of music and art overlap, so it’s not too difficult to translate sound into image. As a bird call rises and falls in pitch, so does my hand. As the volume increases, so does the size of the mark. Round sounds are drawn as ample loops with a soft hand, and sharp, raspy sounds are made with pointed and short marks drawn with clenched fingers. And the concept of rhythm brings these forms together into a unified visual flow.” (Mike Glier)

Tara Donovan

Tara Donovan: Editioned Works, 2004-2016

March 18, 2021 - April 14, 2021

Krakow Witkin Gallery is honored to present a survey of Tara Donovan’s editioned works made between 2004 and 2016.

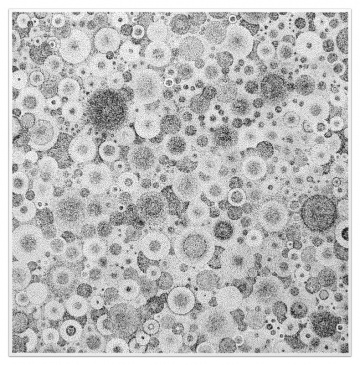

Known for her rigorous process of experimentation, Tara Donovan has earned acclaim for her ability to harness the usually overlooked physical properties of modest, mass-produced goods and transform them, through mass accumulation, into ethereal works that challenge a viewer’s assumptions and perception. Donovan has done this in large-scale installations, discrete sculptures and various works on paper that utilize print processes, often in experimental ways. The results, whether with rubber bands, Slinkys®, styrene cards, or pins, are always open to interpretation and often suggest organic forms. Donovan states, “it is not like I’m trying to simulate nature. It’s more of a mimicking of the way of nature, the way things actually grow.”

Donovan’s many accolades include the prestigious MacArthur Foundation “Genius” Award (2008); and first annual Calder Prize (2005), among others. For over a decade, numerous museums have mounted solo exhibitions of Donovan’s work including the Museum of Contemporary Art, Denver (2018), Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, New York (2015), Milwaukee Art Museum (2012), Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston (2008), Metropolitan Museum of Art (2007-2008), UCLA Hammer Museum (2004), and Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (1999-2000). Donovan’s work appears in numerous public collections including the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Jenny Holzer

Jenny Holzer: Text Works

May 4, 2020 - June 13, 2020

Krakow Witkin Gallery is proud to present “Jenny Holzer: Texts Work,” a selection of works utilizing texts the artist wrote, compiled and presented in different forms over the past thirty-five years.

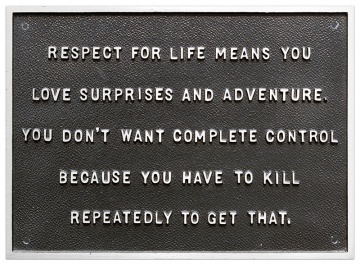

The earliest work in the show is the iconic “Truisms” (1977-79), presented here as part of three different works (two LEDS and a granite footstool). The “Truisms” series was written by Holzer to resemble existing truisms, maxims, and clichés. Each Truism distills difficult and contentious ideas into a seemingly straightforward fact. Privileging no single viewpoint, the “Truisms” examine the social construction of beliefs, mores, and truths. The “Truisms” first were shown on anonymous street posters that were wheat pasted throughout downtown Manhattan, and subsequently have appeared on T-shirts, hats, electronic signs, stone floors, projections and benches, among other supports.

The selection here also includes the 20 sheets from “Inflammatory Essays” (1979-1982). Influenced by Holzer’s readings of political, art, religious, utopian, and other manifestos, the “Inflammatory Essays” are a collection of 100-word texts that were printed on colored paper and, originally, posted throughout New York City. Like any manifesto, the voice in each essay urges and espouses a strong and particular ideology. By masking the author of the essays, Holzer allows the viewer to assess ideologies divorced from the personalities that propel them. With this series, Holzer invites the reader to consider the urgent necessity of social change, the possibility for manipulation of the public, and the conditions that attend revolution.

In addition to these two early bodies of work, there are numerous other pieces, including a metal plaque, several photographs of recent projections, a single etching as well as a suite of etchings from her body of work using redacted material and four LED pieces of different scales. Within the last 15 years or so, Holzer has gone back into her texts and combined different ones so that, while the individual bodies of text continue to cause impact, the juxtaposing of subject matter between texts cause a challenging dialogue. Much like within the early Truisms, where no single viewpoint is privileged, the relationship between the subjects in the various texts provide a non-hierarchical approach to investigation. Not only a survey of the texts used, this selection serves as a display of the varying combinations and dynamic readings of the texts when presented through the different media that Holzer uses.

For more than forty years, Jenny Holzer has presented her astringent ideas, arguments, and sorrows in public places and international exhibitions, including 7 World Trade Center, the Venice Biennale, the Guggenheim Museums in New York and Bilbao, the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Louvre Abu Dhabi. Her medium, whether formulated as a T-shirt, a plaque, or an LED sign, is writing, and the public dimension is integral to the delivery of her work. Starting in the 1970s with the New York City posters, and continuing through her recent light projections on landscape and architecture, her practice has rivaled ignorance and violence with humor, kindness, and courage. Holzer received the Leone d’Oro at the Venice Biennale in 1990, the World Economic Forum’s Crystal Award in 1996, and the Barnard Medal of Distinction in 2011. She holds honorary degrees from Williams College, the Rhode Island School of Design, The New School, and Smith College. She lives and works in New York.

Daniel Buren

Daniel Buren: 8.7 cm

May 4, 2020 - June 13, 2020

Daniel Buren is famous for his use of a repeated 8.7 cm wide stripe that defines, confounds and explores issues of continuity, pattern, recognition and space. The artist has created a lasting body of work that is at once, one continual repetition and yet also a forever changing exploration of comprehension, form and surprise. He began painting in the early 1960s but by 1965, had stopped traditional painting so as to use the the striped awning canvas common in France. Overall, Buren’s works integrate visual surface and architectural space by focusing on the gesture of placement as a way of highlighting the process of ‘making’ rather than a visual/pictorial representation of anything else.

A few key moments in his career:

• Buren started by setting up hundreds of striped posters, so-called “affichages sauvages”, around Paris and later in more than 100 Metro stations, drawing public attention through these unauthorized acts.

• He had his first important solo exhibition at the Galleria Apollinaire in Milan in 1968, where he blocked the only entrance to the gallery, a glass door, with a striped support.

• A year later, without being invited, Buren wished to take part in Harald Szeemann’s exhibition, “When Attitudes Become Form,” taking place in Bern in 1969. Two of the contributing artists offered him space in the show, but he instead covered billboards in Bern with his stripes.

• In June 1970, he put stripes on the front and back of Los Angeles bus benches without permission.

• For his first New York City solo show in 1973, Buren hung a set of nineteen black and white striped squares of canvas on a cable that ran from one end of the John Weber Gallery to the other, out the window to a building on the other side of West Broadway. Nine pieces were inside the gallery and nine outside. A middle piece, which connected the outside and the inside parts of the installation, was placed halfway out the opening where the window frame had been removed for the duration of the exhibition.

• In 1977 Buren cut up one of his artworks from 1969 and made a new work, designating that the sections should hang in the corners of a wall, whether that wall was empty, had doors or windows, or even had other artworks already hanging on it.

• In 1986, when François Mitterrand was president of France, Buren attained leading artist status after he created the 3,000-square-meter sculpture “Les Deux Plateaux” (1985–86) (more commonly referred to as the “Colonnes de Buren” (“Buren’s Columns”), a work in situ for the Cour d’honneur at the Palais Royal in Paris.

• Also in 1986, he represented France at the Venice Biennale and won the Golden Lion Award for best pavilion.

Over his career, Buren has had major solo exhibitions at Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, in 1989, Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris in 2002, Guggenheim Museum in New York in 2005, Modern Art Oxford in 2006, and at Kunsthalle Baden-Baden in 2011, among many others. For the 52nd Venice Biennale, Buren created a new site-specific work for the Giardini of the Italian Pavilion, and was also curator of Sophie Calle’s contribution to the French Pavilion. He has created over 80 permanent public installations on four continents.

Robert Barry

May 4, 2020 - June 13, 2020

Known as one of the founders of Conceptual Art, Robert Barry, in the 1960’s and 1970’s explored sound waves, barely visible string, releasing inert gas into the atmosphere and announcing that exhibitions would be closed. The projects engaged issues of audience involvement, perception, spatial relationships and art world structures. Early on, Barry used written language as art, counter-point and explanation for his work. The use of language soon became his ‘signature’ medium. Barry’s works are, in one sense, austere. Clean words and surfaces provide visual allure. Reading the chosen words provides an opportunity to get into the works and to better “read” the art. However, no defined references exist in the works. One must be willing to question and explore the potential connections, both for the artist, but more so for the viewer. Each of the formal decisions Barry makes provides opportunities for more specific readings of the work, yet there is no one narrative or reference to be made. How the artist makes work that is powerful to look at, captivating to read in their specificity, introspective to explore and yet wide open, is a big part of why the work is so strong.

The texts in the presented works have no one specific narrative or point of departure. Barry has dispersed the words across, over and beyond the surfaces. The arrangements, juxtapositions, and proximities of the words give further opportunity not only to read the words but to read INTO the words to think about what the relationships may be. In some, the reflective quality of the mirrors and mylar reflect imagery and colors in the space, as well as reversing, repeating and spotlighting various elements of the room. How much is on purpose and how much is open to chance is forever unknown. The known, the unknown and the grey area between are key to equally examine in Barry’s work. In order to do this, one must also equally examine the general, the personal and the universal.

Barry’s first solo museum exhibition was in 1971 at The Tate in London and over the years he has proceeded to have solo exhibitions at the Stedelijk in Amsterdam, the Folkwangmuseum Essen in Germany, the former Museum of Conceptual Art in San Francisco, the Musée St. Pierre, Art Contemporain in Lyon, France, the Haags Gemeentemuseum in Den Haag, Netherlands, the Dum Umeni Brno in the Czech Republic, and the Kunsthalle Nurnberg among others. Group exhibitions with Barry’s work have taken place at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, Seattle Art Museum, Jewish Museum, Kyoto Museum of Fine Arts, Museum of Modern Art in New York, among hundreds of others. His works are in the collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY, Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, Panza Collection, Varese, Ludwig Collection, Cologne, Museum of Modern Art, New York, Hirshorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington D.C., Musee National d’Art Moderne, Centre George Pompidou, Paris, Kunstmuseum Basel, Basel, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Museum für Monderne Kunst Frankfurt am Main, Frankfurt, Germany, Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles, Los Angeles, and the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, among many others.

Sol LeWitt

Sol LeWitt: Forms Derived from a Cube in Two and Three Dimensions, and One Wall Work

January 8, 2020 - February 29, 2020

To begin 2020, Krakow Witkin Gallery proudly announces an expansive exhibition of Sol LeWitt’s work. Through structures (LeWitt’s terminology for his three dimensional works) and gouaches, the exhibition displays forty years’ exploration of the cube. In addition, a large wall piece (“White styrofoam on black wall” from 1993) provides a bold contrast to all the rectilinear forms.

The exhibition contains an ‘open form’ structure, a ‘closed form’ structure, a ‘progression’ and an extremely rare 1968 “Hidden Cubes” structure that has never previously been exhibited. The works on paper present two ways LeWitt drew/painted cubes — isometric and trimetric. Furthermore, the different pieces help illuminate the processes he used to layer color on paper to create the variations of tone, positive/negative, foreground/background and surface/depth. By not using illustrative perspective, LeWitt honors the flatness of the paper by presenting all visible sides of the cube and the background as equal.

This sense of equality is key to understanding LeWitt’s work from the date of the first piece in the show (1968) to the last (2005). Visible and hidden, monochrome and polychrome, 3D and 2D, and numerous other seeming dichotomies are treated by LeWitt as mutually significant. LeWitt’s longtime assistant, Susanna Singer, describes LeWitt’s overall practice as ‘using a vocabulary to create language.’ This exhibition gives the audience an opportunity to revel in his language and hopefully celebrate the curiosity with which LeWitt approached life.

One Wall, One Work: Robert Barry

September 21, 2019 - November 2, 2019

Giulio Paolini: 1983-2010

September 21, 2019 - November 2, 2019

Shellburne Thurber: Phantom Limb

September 21, 2019 - November 2, 2019

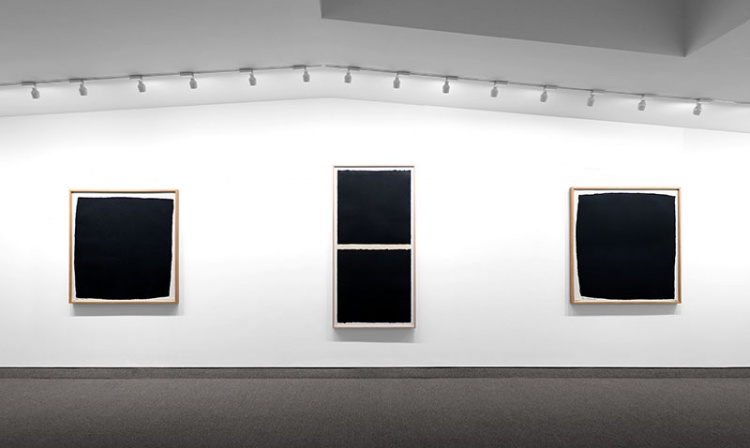

Robert Ryman

1969-1994

June 22, 2019 - July 26, 2019

Terry Albright

Sculpture, 2015-2018

June 22, 2019 - July 26, 2019

Amy Stacey Curtis

One Wall, One Work

June 22, 2019 - July 26, 2019

Mel Bochner

Mirror Works

May 11, 2019 - June 15, 2019

Josef Albers and Fred Sandback

May 11, 2019 - June 15, 2019

Sarah Charlesworth

The Small Versions, 2000-2012

March 30, 2019 - May 4, 2019

Journeys

March 30, 2019 - May 4, 2019

Sol LeWitt

One Wall, One Work

March 30, 2019 - May 4, 2019

Robert Mangold

1979

February 16, 2019 - March 23, 2019

Facing Grain

February 16, 2019 - March 23, 2019

Kay Rosen

One Wall, One Work

February 16, 2019 - March 23, 2019

Thomas Ruff

press++

January 5, 2019 - February 9, 2019

William Kentridge

One Wall, One Work

January 5, 2019 - February 9, 2019

Back to all Member Galleries

Back to all Member Galleries