Cavin-Morris Gallery

529 West 20th Street, 3rd Floor

New York, NY 10011

212 226 3768

New York, NY 10011

212 226 3768

Cavin-Morris Gallery was founded in 1985, and our first gallery was on Hudson Street in Tribeca. Five years later we moved to 560 Broadway, which was home for fifteen years. We then moved to 210 Eleventh Avenue, for another fifteen years before finally moving to 529 West 20th Street, in April 2021.

The Gallery has been exhibiting contemporary artists from around the world for almost 40 years. We specialize in the work of contemporary artists who do not intentionally make art for the art world mainstream canon. We represent past and new generations of artists whose work ultimately feels timeless to us.

We also concentrate on both functional and non-functional contemporary ceramics. We are especially interested in the way certain ceramists push the envelope in their expression of traditional forms and cultures. We show work by Western ceramic artists, as well as works by artists from Japan, Korea, and China.

The common thread that connects all this art is its uniqueness, its integrity, visionary authenticity, the intermingling of spirituality with nature, and its reflection of cultural homeground. We look for the place where labels become irrelevant and the work remains urgent, immediate, and singular.

Installation view of Cavin-Morris Gallery.

Davood Koochaki

Dancing in Plain Sight: Late Drawings by Davood Koochaki

January 11, 2025 - February 15, 2025

DANCING IN PLAIN SIGHT: LATE DRAWINGS BY DAVOOD KOOCHAKI

(January 9 – February 15, 2025)

Cavin-Morris Gallery is thrilled to present a one-person exhibition of the drawings of the Iranian master Davood Koochaki.

Davood Koochaki was born in 1939 in the province of Gilan in Northern Iran. He died in Tehran in 2020. His life wasn’t easy. At six he dropped out of school to help his family working in the rice paddies they maintained for others. He worked extremely hard all his life and saw drawing as his late occupation. Although illiterate, he remained intellectually engaged with the world, always seeking out creative people to talk to.

He moved to Tehran when he was 13 and eventually became an auto mechanic, marrying and raising a family. He began to draw in his 40s but did not pursue it seriously till he was in his sixties.

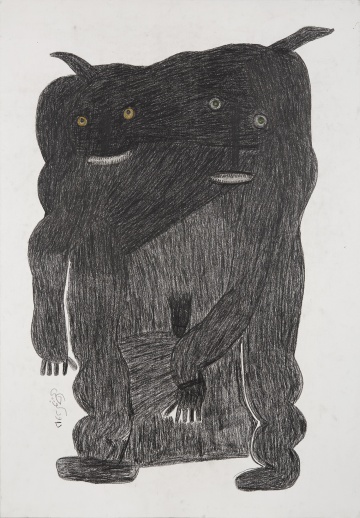

He grew up surrounded by the rich Persian folklore which animated the daily war between Good and Evil, often using animals to symbolize moral forces, for example snakes as symbols of evil and birds as signs of good omens. Nature was the stage for playing out the eternal stories of struggle.

We can see this movement of forces in most Koochaki drawings. Like other Art Brut artists, he allowed his memories, anxieties, dreams fears, and joys as well to come to the bidding of his drawing hand. He didn’t talk much about the precise meanings and symbols in the drawings, but his process was time-consuming and was a way of conquering time and letting it pass.

Much Art Brut comes from the expression of inner and outer repression. We see the results of the horrors of the two world wars’ unprecedented brutality in the moving histories of the inmates of post war mental institutions. A well-known example is Carlo Zinelli, who suffered a breakdown during the Spanish Civil War, resulting in a lifetime spent in a mental institution in Verona. Fortunately, he was able to exorcise his demons by drawing, an activity he was encouraged to do. In what is now the Czech Republic we know Anna Zemánková and Miroslav Tichý both evaded the worst of Soviet occupation, along with many others, via their art making. We know the reactions in the United States and Caribbean to the forces of slavery, racism and colonialism, whether we look at the Vodoo religion-infused paintings of Hector Hyppolite, or the scarcely disguised aggressive persecutions we see in the paintings and drawings of Bill Traylor. Many of these artists were championed by Jean Dubuffet and included in his nascent Compagnie de l’art Brut.

Art Brut creators, appear in all classes of society, but aside from those who had psychiatric problems, some of the most powerful work came from blue-collar and poor workers who could no longer cope with the system. In the case of political repression art becomes a way of proclaiming the self-and/or making difficult time go by. However he focused mainly on European artists, and it wasn’t until the mid 1940s that attention began to be paid to non-European artists.

What makes Koochaki so great is his ability to voice nightmares and the good points of humanity at the same time. We are beings of contrasts and inconsistencies; we contain multitudes. We suffer and triumph, often simultaneously. Koochaki was a visual storyteller. He laughed and talked whether he drew dark or light subjects. He would often regard his finished drawings with bemused surprise, as if caught off-guard by his own intensity. Indeed, Koochaki was as amazed by what appeared on the paper in front of him as anyone. If you see videos of him while drawing made by his advocate and friend, Morteza Zahedi you will see Davood’s paternal pride in his drawings but also an obvious sense of rebellion and mischief.

Davood Koochaki put his demons and angels into a personal visual language that is unique in our field, as if they were painted on the cave walls of his haunted memories. Like all our anxieties they loom and move in a dance that alternates between the dark and the light, called down for us by the heart and hand of a truly great artist.

Back to all Member Galleries

Back to all Member Galleries